Looking for that perfect Christmas gift for the family? Why not a chicken? Stick a bow on top, put the chicken under the tree, and who knows, you may even have a couple eggs to fry up for breakfast Christmas morning.

Give the gift that keeps on clucking. A chicken. Okay, maybe it's not the perfect gift for your family, but it is the perfect gift for a poor family in Asia. A chicken can break the cycle of poverty for a poor family. Yes, a chicken.

A chicken's eggs provide food and nourishment for a family, and they can sell those eggs at the market for income. When you donate a chicken or any other animal through Gospel for Asia, 100% of what you give goes to the field. And the best gift of all, when Gospel for Asia gives a poor family an animal, it opens the door to the love of Jesus. So give the perfect gift for a family in Asia this Christmas. Give them a chicken. Call 866-WINASIA.

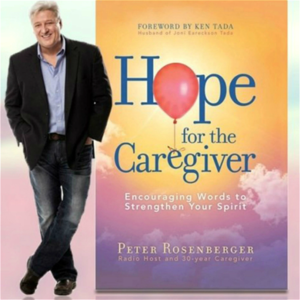

Or to see chickens and other animals to donate, go to CritterCampaign.org. Hey, this is Larry the Cable Guy, and you are listening to Hope for the Caregiver with Peter Rosenberg. And if you're not listening to it, you're a communist, Peter Dodd. Welcome to Hope for the Caregiver. I am Peter Rosenberg. This is the nation's number one show for you as a family caregiver. How you doing? How you holding up?

What's going on with you? We are so thrilled to have you as part of the show. If you want to be a part of the show, 877-655-6755.

Guess what? You'll also get to talk to himself, the man who brings joy and laughter to children of all ages. He is John Butler, the Count of Mighty Disco, everyone. John, how you feeling? Oh, I am just grand as always. And you know, if there's something I can do for this planet, it's bringing joy to children of all ages from zero to 109, or whatever the Lego thing says is appropriate.

Zero to 109. Well, John, I have a special treat today. You have many fans on this show. You know that.

Oh, well, I'm glad. I have received notes from all of them, and they said if John wasn't on your show, it'd be revolting. But I do have, one of them is our dear friend Elizabeth up in Prince Edward Island. And the other one is the guy that I have on the phone here now. And he is one of my closest friends and his name is John as well.

But we're going to go with JP on this. And I asked him to come on the show. He's told me often, he said, I just want to meet John Butler. I just want to meet. And he said, I really don't care about you, Peter. I just want to meet John. Oh, I know you, Peter.

This is fine. But it's, I was thinking about, John and I have been to Africa together, and JP and I have been to Africa together twice. And he's been out here to spend time with us in Montana. And we've just, we've developed a very, very close friendship over the last 10 years. He and I share a lot of common life experiences and a lot of common things that we banged around ideas for being healthy individuals in the midst of some real craziness. And he's been a great source of encouragement to me. But he's got some wisdom on some things that I felt like would be appropriate today for the audience.

We touched on this a little bit last week, and so I want to continue to just bore into it. But first I want to welcome to the show. JP, how you feeling? Hey, I'm doing very well.

And John Butler, he's absolutely right. I cannot wait till I finally meet you. We've talked many, many times on the phone. I enjoy your personality. I enjoy your contribution to Peter's show. And so all that is true. And I hope I'm not disappointed when I finally get to meet you. It is my distinct and singular pleasure to be able to give some value to this particular program. Right. Well, you can see why Peter and I get along, right? Because we're cut in the same class. Just fell right into it.

I speak fluent sarcasm. And I apologize to all the listeners streaming this right now on social media. There's a fuzz to the feed that I cannot seem to work out.

When I log in with it, it does fine for about a minute and then it just goes fuzzy. But the podcast itself will be clear because it is in Dallas and it is running this whole operation and he is doing a spectacular job of it. So if you're fuzzy on the feed, you could always get the podcast later on at caregiverpodcast.com.

Just go out there. The podcast is free. Download it on any podcast player. And today is the, when we record the podcast, we do something a little bit different. On my Saturday show, it's all broadcast and we take a lot of callers and that kind of stuff. But on the podcast, we open up the conversation to have what I like to think are in-depth conversations about particular topics. And we don't, there's no rehearsal. There's no scripting as if we could.

That would require work, you know. And I'm also coming to you with a mea culpa to begin off, to begin the show with, because Gracie said to me last week, you know, you talked over John Butler a lot last week. And normally I could see John because we have a video monitor, but last week he didn't have it.

So I couldn't see him and I was going blind into this. So, but I will try not to step on John's toes. Oh, back at you. And I don't, I do not, you know, I try to keep the flow nice and even, and this is your show, don't get me wrong, but you can blame Apple for that, you know.

But I love this format where we can talk about these things and get in depth. John, JP and I've been talking a lot this week and the last couple of weeks actually, because I have really struggled postoperatively more than I've really let on. This has been a journey for me and I know it was just my knee, but it seems like it threw everything out of whack for me. And I have, I've gone now almost three months without sleeping the whole night through.

And that's been a tough thing for me. Last night I actually went to bed early and I woke up several times a night, but I never got out of bed for nine hours. That's the longest I've gone now because I was just so tired and I thought, okay, that's progress. It's not just my knee, it was my whole body.

I mean, my shoulders, my arms. And I was talking to, John brings an orthopedic surgeon background and I was talking to him, but my fingers are going numb because obviously something's thrown off kilter and pinched into my neck and everything else. And I called him up and I've just asked him a lot of just general questions orthopedically, but then we got into a conversation about sleep deprivation. And he, you and I touched on that last week, just a hair. And John started sending me, JP started sending me some stuff about this.

And so now he's got his own caregiver journey. We're going to get into that in just a minute. But I want to start off this segment and I just want to delve into this because this is something that JP has personally wrestled with himself. He's an extreme athlete.

Have you heard about these things called Tough Mudders? Well, JP is this guy. I mean, he's insane about it. And he's an extreme sports guy.

And there is this, and he's told me there's often this macho-ness in those kinds of things of how far you could push your body. But then wisdom brought him back to the table where he said, you know what, this is not appropriate. This is not healthy. And I'm looking at caregivers and I think it wasn't wisdom. It was failure. It was injuries.

It was a mental breakdown. I wanted to call it wisdom. Wisdom is the result of all of those facts. We crawled to the table. We walk away with wisdom. But he started sending me some stuff about it and talking about it. And I thought, how many caregivers, how many caregivers are pushing themselves to the breaking point?

And not getting sleep. So, JP, first off, I want you to know this is a treat to have you on here. And it's a treat to have you on here with John, two of my closest friends. And delve into this. Just jump in. The audience can keep up because this is a smart audience.

So, just delve into it and go. Well, and I'd like to open by saying that if we talked two or three years ago, I would not have been able to contribute anything to sleep. Because I was under, I think the thing that really got me convinced or got my attention is I was listening to, I'm very fond of Navy Seals. And it was a Navy Seal podcast. And a gentleman by the name of Dr. Kirk Parsley, who was a former Navy Seal who then went back and started treating a bunch of Navy Seals with PTSD.

And it's a long podcast. And just to synthesize it, he basically looked at all of their symptoms. And he described, and actually I was pulling into my driveway, and he described me.

He described all these men. I actually stopped the podcast, replayed it, and I played it. I said, honey, who does this sound like? Not knowing anything about the podcast, who this guy was, he starts ripping down lack of motivation, can't control your body composition, sleep difficulties, labeled moods, snapping at the kids, relationship issues with your wife, not as strong, decreased libido. And I said, who's that son?

She goes, that's you. And I said, he's describing Navy Seals that are suffering from PTSD that all have sleep difficulties and all different situations going on. And he actually was able to find out that their real issue was just sleep.

That's all. And he revolutionized these guys' lives. He's revolutionized Navy Seal training and PTSD treatments. And had it not come from somebody who I respected who also has this kind of bravado about sleep and sleep is for the weak. We used to joke, when I was a resident, we used to joke, well, sleep is for the weak. And we used to stay up routinely, 36 hours, 48 hours, and we could do it. And we were killing ourselves.

We were destroying our bodies, but we were these macho, we were orthopedic surgeons, and we can do this, not realizing what we were doing to our bodies. So when I heard this coming from somebody who I could respect, who was a Navy Seal, who did do the same kind of silly things that I've done in the past, it really struck a chord, I should say. And I really started paying attention to this. And I started realizing that this is something I've got to get a handle on because my sleep was, you know, the average sleep is 6.2 hours a night for Americans, which is terrible, which is two hours less than we all need.

Mine was much less than that for years. And it was killing me. Butler, have you ever, has this been an issue with you with sleep? Well, when I was, this is one of the things that strikes me is like that, yeah, that I hear that doctors in residence, this is part of the culture, you know, like, yeah, we're going to do this.

And that's kind of, yeah, kind of the last thing I want somebody who I'm going to get into a knife fight with while I'm asleep to be like, you know, I want you to be skilled. I was never asked once, but I worried about it. I was never asked once by a patient, how long have you been awake, doctor? And I always feared that question.

What am I going to say to this family? Am I going to lie to them and say, I just got eight hours of sleep? You know, when I've been up for 36 hours. I never got that question asked, but I worried about it. Well, I am generally a pretty healthy person these days. I haven't, you know, had a surgery since I was a child or anything like that. But should it happen in the future?

I know what question I'm going to be asking. Well, I would say that's more residency training. I think attending physicians get a better handle of their lives and, and do a better job of sleeping. But so that's more residency training. And so I don't want to throw doctors under the bus. I love my doctors who have put my body back together and give me my life back and a neurologist who fixed the herniated disc in my back, which literally gave me my life back 10, 11 years ago. So I don't want to throw doctors under the bus.

No, but I get the culture, but pivoting this into caregivers, I look at the pace that so many that are taking care of their loved ones are dealing with. And there's one principle I want to lay out that sleep ain't rest. Rest and sleep are two different things, two different things. And we could sleep hard, but then we wake up just as tired and as groggy because we're not resting.

But we'll get into that in just a moment. But I was over 20, gosh, 23 years ago, Gracie had been on a lot of heavy medication and was sleeping pretty hard through the night. I, on the other hand, didn't know any different. And I knew that I snored. My brothers always teased me about that when I was growing up, but I didn't know that I had sleep apnea.

And so I was, and then when she came off of some of that stuff, she noticed that I would stop breathing in the middle of the night. And then if I ever took a nap, I would wake myself up thinking I was snoring and I'd feel refreshed. But what happened was I would stop breathing, my heart would kick in and then adrenaline goes to my heart and it wakes me up and it makes me feel like I got energy. But in reality, I did not have energy. In reality, I was just destroying myself one snore at a time, one gasp at a time. And so I went to a sleep disorder clinic and they tested me and so forth. And then since then, I've used a CPAP machine and it's the way I have to do it.

I have to sleep with that because it changes my personality if I don't. It changes everything about me. And we've lost people that have physically died from the exertion on their heart.

Reggie White, for example, used to play football for the University of Tennessee, then went on to play for Green Bay. And this stuff takes a toll on you. And so I thought about how many of my fellow caregivers are not properly diagnosed with any type of sleep issues at all because they're just pushing themselves to the break. So I want to spend some more time on this just talking about, okay, what's the next step? How do we learn this? How do we find out? This is Hope for the Caregiver. I'm Peter Rosenberger.

I'm on with my dear friend JP, John Paradis from Connecticut, and also my dear friend John Butler from Nashville. And we'll be right back. In 1983, I experienced a horrific car accident leading to 80 surgeries and both legs amputated. I questioned why God allowed something so brutal to happen to me.

But over time, my questions changed and I discovered courage to trust God. That understanding, along with an appreciation for quality prosthetic limbs, led me to establish Standing with Hope. For more than a dozen years, we've been working with the government of Ghana and West Africa, equipping and training local workers to build and maintain quality prosthetic limbs for their own people. On a regular basis, we purchase and ship equipment and supplies.

And with the help of inmates in a Tennessee prison, we also recycle parts from donated limbs. All of this is to point others to Christ, the source of my hope and strength. Please visit StandingWithHope.com to learn more and participate in lifting others up.

That's StandingWithHope.com. I'm Gracie, and I am standing with hope. Welcome back to Hope for the Caregiver.

I am Peter Rosenberger. This is the show for you as a family caregiver. That's Gracie, my wife, from her CD Resilient. And go out to StandingWithHope.com. You can see more about it and be a part of what we're doing through this show, through the prosthetic limb ministry that you've heard her talk about. And we'll send you a copy of that.

Whatever's on your heart to do, we'll send you a copy of her CD. I think you'll find it very meaningful. We're talking to my friend JP from Connecticut and John Butler, of course, about sleep and the challenge for family caregivers who have pushed themselves. And some of the things that we're going to find out about ourselves if we're not getting enough sleep. And one of them is you're going to tend to be pretty irritable. You're going to also tend to lean towards some depression. And these are things… I'm not a medical doctor. I don't have any training in this.

John, of course. I mean, JP does, but I don't. But I've lived it, and I know what happens to you if you're not getting rest. Well, it's a quick path to temporary psychosis.

It is. In fact, Star Trek The Next Generation did a whole series on this. I mean, a whole show on this. You remember that one, John? Yeah, yeah, yeah. Where the species that didn't sleep? Or they had edited out?

No, no. It was that frequency that they couldn't get into REM sleep. Remember that? And they were trapped in that. And the only data was they had to get them out of that vortex. But I digress into nerdville. Of course.

But one more thing before we hop that train out of nerdville. Even the Borg sleep. So… But when we do sleep, and we get good, healthy sleep… And I was getting to the point where I wasn't sleeping so well, and I have a ton of Mike Lindell's My Pillows. And I was getting ready to write him a stern letter. Because I wasn't getting any sleep, and I'm thinking, dude, I see your commercials all the time.

What's going on with this? But it was really starting to trouble me. It wasn't the pillows. Those are fine pillows, all right?

They are fine pillows. And if you mention the word caregiver, when you order one, you'll get a discount. I'm just saying. No, there you go.

That's what I was prompting there. JP came in, and he started laying it out. And he said, okay, look here, Peter. This is what's going on with your body. And I haven't had too many medical issues. And it's been 11 years since I had anything. I had my appendix ruptured 11 years ago, and I had to go to the hospital.

And it was some similar things. But this thing right here, for whatever reason, I've been gimping along on this leg for so many months now. And then once I got it operated on, everything just kind of went haywire with me. And I thought, well, why is this happening?

This is just a knee surgery. And that's when JP laughed at me. He said, no, dude. Well, tell me what you said. Just tell the audience what you said to me when I called you just a couple days ago.

I called you yesterday. You said, this is what's going on with you. Yeah, it's when sleep is… Well, just about operating on my knee. When you talked about my knee. When I said, why are my shoulders and everything else hurting when it was just my knee? Oh, man, I don't remember what we were talking about.

Then I'll finish it for you. Well, what you said was… We go on all night, so… Well, that's true. But one of the things you said to me that was rather poignant was, you said, when I was younger, I used to kind of make fun of alternative medicine people. Because I thought that the chiropractors and the acupuncturists and all that stuff, I said, I thought that was just kind of hoping.

And then he said, but I've come to realize that we don't know a whole lot. And everything in our body is connected. And when you majorly invade one part of it, the rest of it gets wacky. It can get wacky.

Yeah. And there's always compensating. And there's always when you… There's referred pain. You can have a knee pain that's not even knee pain. It's just a hip pain that's going down to your knee. You can have a shoe that's a bad shoe and you start limping. And now you start throwing your back out of whack. But really, all it is is a bad pair of shoes that's throwing your pelvis out of whack.

So, yes, everything is connected. And that stuff, since then, I've been out of medicine for 20 years, just to let your audience know. But that stuff, and a lot of this, like with the sleep hygiene and the sleep research that I've looked into, is long after medicine. Because in allopatric medicine, which is typical medicine, you don't practice that. You just fix diseases, you fix broken bones, and you send people home.

You don't prevent anything. And that's a big criticism, I think, of medicine and the American medical kind of community. But it's just kind of where we are as a country. We want to live however we want.

We want to eat whatever we want to eat. We want to sleep as little as we can and just go to the doctor and say, give me a pill to fix it. So, I really don't blame the doctors. I blame us.

I blame the patients, and I blame society. But these things are connected. And the old silly song, the leg bones connected to the hip bone and all that, that's kind of a silly cartoonish way to think of it. But we are all connected. And hormonal balance and all of that.

If we're not getting enough sleep, our brains are not regenerating, our neurotransmitters are not regenerating. We can't think. We can't handle emotional overload. We can't handle stress. And we're doing that to ourselves over and over and over. If you stay up all night, say like what we do at those World's Toughest Mudders, when we do the 24-hour events, by the middle of the night, I'm hallucinating. I'm talking to people who aren't there.

I'm literally, no, not literally, because my blood alcohol level isn't there, but I'm functionally drunk. And it's amazing how, you know, what we do to ourselves, you know, in those crazy races or whatever. That's a one-time kind of short limited thing. But we live our lives like that. So we're trying to function being impaired, just like trying to drive a car after you've had six beers or four beers or whatever the case is.

You can't do it. And you can say you can do it and you might get lucky and make it home, but it's a disaster. And being sleep-deprived is the same thing as being impaired with alcohol. Well, I looked at a lady, John, the other day at the grocery store. I was talking to her and she'd been, you know, checking on us with my surgery and so forth. And I looked at her and she looked exhausted.

And I said, how are you doing? And she said, I haven't had much sleep because we have a son with night terrors. And I thought, and then she said, this is our second child to go through that.

And it just keeps us up. But then I talked to parents with children with autism. And at night, those children will elope sometimes. They'll just walk out of the house. And so they sleep kind of on edge because they're wondering, is the child going to get up and leave the house? So they have to do special things to make sure the child stays in bed. And I thought these parents are, I mean, bless their hearts. I mean, you know, that is no way to live.

And yet that's how they're doing it day in and day out and day in and day out. So I thought we got to have a conversation about this, what this looks like to get some sleep. How do you protect your children so they stay in the room while you go get some sleep, you know, that kind of stuff. But we can't keep pushing ourselves to these extremes. And so this is, you know, we're going to go to the break here in just a second.

But I just wanted to have this dialogue so people understand that this is not something we need to white knuckle ourselves through. Sleep is important. We'll get to the point where we're talking about rest a little bit later, but sleep. And if you even think you have a sleep disorder, please see your physician.

Please see your physician. This is Peter Rosenberg and this is hope for the caregiver. We're talking with John Butler, of course, the Count of Mighty Disco and my dear friend John Paradis from Connecticut. Listen, healthy caregivers make better caregivers.

And part of being healthy is getting a good night's rest. All right. We'll be right back. She had this vision for using prosthetic limbs as a means of sharing the gospel to put legs on her fellow amputees. And that's what we've been doing now since 2005 with Standing With Hope. We work in the West African country of Ghana, and you could be a part of that through supplies, through supporting team members, through supporting the work that we're doing over there.

You could designate a limb. There's all kinds of ways that you could be a part of giving the gift that keeps on walking at standingwithhope.com. Would you take a moment to go out to standingwithhope.com and see how you can give?

They go walking and leaping and praising God. You could be a part of that at standingwithhope.com. As a caregiver, think about all the legal documents you need. Power of attorney, a will, living wills, and so many more. Then think about such things as disputes about medical bills. What if, instead of shelling out hefty fees for a few days of legal help, you paid a monthly membership and got a law firm for life? Well, we're taking legal representation and making some revisions in the form of accessible, affordable, full-service coverage.

Finally, you can live life knowing you have a lawyer in your back pocket who, at the same time, isn't emptying it. It's called Legal Shield, and it's practical, affordable, and a must for the family caregiver. Visit caregiverlegal.com. That's caregiverlegal.com.

Isn't it about time someone started advocating for you? www.caregiverlegal.com, an independent associate. The plans he has for you. Welcome back to Hope for the Caregiver. This is Peter Rosenberger. That's my wife, Gracie, from her CD, Resilient.

Get a copy of it today at standingwithhope.com. We're talking about rest, sleep, two different things, and I've got my friend JP from Connecticut here, and I've got, of course, John Butler, the Count of Mighty Disco. I've got two Johns here. That's why I call them one JP. Both of them have the nickname JP, so it gets a little bit weird. If you're listening to this podcast, first off, you know that weird is our middle name. JP, you've recently gone through a long stretch as a caregiver with your dad. I don't want you to expose anything. I don't feel obligated to give any kind of personal stuff, but I would like for you to share some thoughts you had on what happened to you through this process.

How did you change through this process, and where's your head space and heart space on this? Yeah, well, it's interesting because you and I have been friends for a long, long time, and our friendship had nothing to do with caregiving. It was just a crazy thing.

Thank God for Rush Limbaugh, who introduced us to each other. True story. It had nothing to do with it.

That's a true story. It had nothing to do with caregiving. Then in May of 2017, my dad had a hypertensive stroke. He was on some blood thinners for his AFib.

That was kind of the warning shot over the bow. They finally agreed, my parents after years of us trying to get them to move in with us. They agreed to move in with us, which was a very good thing. Then in September of 2017, he had his real stroke. He had an embolic stroke, and he was pretty much non-ambulatory. Very uncooperative with the PT and the OT people. Actually, I kind of saw him check out. Once he moved in with us, he knew Mom was okay. She's going to be, you know, John's going to take care of her.

I did my job. I think there was some depression and some other things going on that we probably didn't pick up on. But anyway, he had that significant stroke, and he just continued to fight with his therapist and continued to be uncooperative with his PT and OT. It got worse and worse until early January, where he likely had another stroke, although he really wasn't diagnosed. But just looking at him and functionally, he then was bedridden and then accelerated his demise until his passing in October of 2019. So that's kind of the history and the natural course of his history from his first stroke to his passing in October of 2019. Where I kind of got involved and where I saw this, it was very, very tough to watch that.

My mom was the primary caregiver, although all of us contributed to that. I went through a lot of emotional things and a lot of anger. Just watching him give up and watching how hard he was making light for my mom. And I resented him for that.

And I'm not proud to admit that, but I just have to be honest. And Peter, you and I talked a lot about this. You helped me, gave me some incredible counsel. But you know, I was really angry and dealing with all these. And then I had some personal stressors, and we had to buy my parents' house from them to protect their assets.

And so we had some financial pressures. I lost my office manager of 10 years. I had a bunch of injuries. I wasn't able to do these tough mutters, which had become a coping. It had become a drug for me. So I was doing all these tough mutters and doing all these crazy things, but it really was just an outlet for me. But with all these injuries, as my body was breaking down and as my stress in my life was increasing, and as I was sleeping less and less and less, I just completely broke down. And so I kind of collided with caregiving in a very, very tough way. And I became that person out there that desperately needs a show like this and desperately needed support. And thank God, you know, Peter and my wife and people kind of stepped in, and I went and got care. And I actually was diagnosed with PTSD. I had what, you know, back in the old days they call a nervous breakdown, an acute reactive depressive episode, and started taking medication, seeing a psychiatrist, which I still see.

And I'm not embarrassed at all to admit that. He's been a lifesaver. And also with some therapy and implementing a lot of other changes in my life, including sleep. So that was kind of my – you talked about how I gained wisdom. That was my introduction to wisdom.

And it came in a very violent way. You know, as I watched my dad, his demise, and I watched my mom take care of him, and it was just very, very difficult to kind of watch this. And it gave me an added respect for caregivers and for Peter who has been doing this for 30 years. And so caregiving is not for cowards.

It's a very – I like that one down. It's going to expose your weaknesses. And it exposed my weaknesses. And in retrospect, a year and a half after, I'm off my medications doing much better, not self-medicating with alcohol, not doing all these destructive things. Up until about a month ago, I hadn't even taken an ibuprofen. I've been very healthy. I've been training completely differently, been taking care of my body, been sleeping. And I think sleep is the number one thing that I've done for myself. I did get a German Shepherd dog, which is a wonderful PTSD therapy dog. And she's been a lifesaver for me.

So I've made significant changes in our lives. But sleep was a terribly important component of that. And what I learned through caregiving was it is rough, and it is going to expose your weaknesses, and it's going to break you, especially if you're combining it with sleep deprivation. And one thing, just to take a look, and we're trying to hammer home the importance of sleep here, and I hope we're doing it, but if you ask most people what the number one interrogation tool is for terrorists or military, whatever, people would say, oh, probably waterboarding. It's sleep deprivation. They use sleep, and that's what breaks people more than starvation.

Sleep deprivation is what the CIA uses and what the government uses and what military intelligence uses to break prisoners. And so it is – and we do that to ourselves. John, I've watched – and I've watched this with fellow caregivers and myself, and this is one of the reasons I just wanted to have this conversation today.

And I don't want to belabor the point, but I think it's very important for a couple of reasons. I think that caregivers who do this in – we're all isolated, so we think it's all – we're the only ones going through this. And so I wanted other caregivers to hear stories to say, okay, look, this is not just me. I mean, you're a consummate professional, very successful at what you do, and you were pushing yourself. You're a smart man. You're one of the smartest guys I know, and yet you were pushing yourself to extremes. And I look at folks who are doing this with special needs children. I look at folks like this lady with the – kid with the night terrors and children – family members with children with autism and so forth, and they're pushing themselves and pushing themselves. This will not end well. One of two things are going to happen, and usually they're bad. And so what I'm asking my fellow caregivers is to take a moment to really take heart to these words that we're sharing.

Here are two guys that are telling you what sleep deprivation is, what it does to the human body, what it does to who you are, your relationships and everything else. And I've got enough skin in this game to say this is the deal, and you must, must respect the trauma being inflicted to your body. And then go see your doctor. That is one of the first things that I tell fellow caregivers. Go see your physician. When's the last time you saw your doctor? And be candid with your doctor. Please, don't be embarrassed.

Please do not be – and if your doctor treats you any way disrespectfully, get another doctor, okay? And you cannot be embarrassed by this. You have to understand how much trauma is being leveled at your body if you're dealing with these kinds of things. And so – and then as John shares his own journey with what happened with his father, it was a catalyst for several things in his life, and there's nothing like being a caregiver to expose the gunk that's in your soul.

And it's just – there's nothing like – because it will find – like you said, it will find those weak spots and amplify them. I mean, it is – it intensely comes after it. And so I just wanted to have a – like I said, a candid conversation about this physical need of sleep that we caregivers often overlook that we just – we are running. And when we get a break from taking care of someone, we don't know how to just stop and be cool for a while. We sit there and our nerves are just frayed and all these kinds of things.

Butler, you were going to say something. Yeah, there's – and I know that we're kind of talking more about problems than solutions here for – about how much we want to emphasize how important sleep really is. But I mean, you can logic your way through this without even having to deal with it. Like the brain is – it's tissue. It's part of your body. Your muscles are part of your body. Your organs are part of your body.

And the brain is awfully complicated and like – okay, let's say you're a lifeguard. Stick with me on the metaphor. All right, Peter. I'm here, baby.

I'm here. Yeah, yeah. You're a lifeguard and you don't have proper nutrition or whatever and you get a cramp going to save somebody.

Well, where does that leave that person? Yeah, well, if your brain doesn't get a sleep, it's going to get a cramp in quotation marks and you're not going to be able to think straight about anything. So, proper nutrition and proper sleep hygiene and everything is just so important and the brain is, if not – it's certainly not immune to these things. In fact, it's probably more susceptible to these sorts of things because of how complicated it is. Well, and you think about the task we do as caregivers, medication administration.

You know, I mean all these kinds of things that we do and it's – you know, these are things that are important things. Now, I want to pivot real quick and we'll take the rest of the show on this to talk about rest because sleep ain't rest. Now, we've talked about the importance of getting sleep and if you feel like you are just run down as a caregiver and you're listening to this for the first time… Yeah, wrap that up with the practical advice, you know. The practical advice is go see your doctor, make the call, pick up the phone and call your family care physician, primary care physician, internal medicine doctor and go see this physician and say, look, I am under so much stress, I am a caregiver and I'm not sleeping well, I don't know if I have a sleep disorder or whatever.

If they blow you off, you're going to have to get another doctor, okay? Yeah, because you're probably sleep deprived and not thinking straight anyway, so… Yeah, keep… Or they're not very well versed in it because they will have to get and have an interest in it and actually do some extra homework because I did not have – I don't remember a single sleep lecture in medical school, not one. No nutrition, nothing on sleep. It's not taught in medical school.

Well, and that is highly unfortunate. Find a doctor who cares about sleep and understands its value and has done his own work after medical school. And if you've got to start off with a counselor at first, a counselor can refer you to a doctor that that counselor knows that takes this sort of stuff seriously.

So there's paths to do that, but the point is, as a caregiver, you have – please take charge of this issue and make the phone call. Okay, that's for sleep. That's what your body needs is sleep. Now let's talk about rest because that's what your soul needs. And that's a little bit different because when you go lay down in bed and maybe you even get a good night's sleep, I mean as far as eight hours, but you wake up and you're not rested because you're in such turmoil internally.

How are you dealing with that? And I know this is a part of where you came in, J.P., that when you're dealing with PTSD and these kinds of things, you can get some sleep maybe, but are you resting? And even through the day, you just stay so keyed up and you're just – and I look at the tension that I'm living with now that it's affected so many parts of my body. And after a surgery, a knee surgery that was outpatient and I'm thinking, why am I like this?

Why am I so crippled up like this? And I realize that I'm not resting and resting is a sole decision. That is intentional that you're going to say, okay, I'm going to learn to be at peace with whatever's going around me. I don't have to calm the storm down. I just have to calm me down.

The storm will pass. I need to be calmer and I need to breathe differently. I need to think differently. I need to retrain my mind.

And I don't think I can do this, but I know I can't do this on my own. That's where my faith comes in. And that's also where it comes in with having people around you that are supportive of this that are constantly reinforcing this because we're going to get reinforcement either negatively or positively. And the reinforcement positively is slow down, take a breath, just slow down, slow down because we are absolutely pushing ourselves to the breaking point on a soul level and on a physical level.

John, JP, jump in on that one. Yeah, one of the practices that I started, which I think dovetails perfectly into this, is I started a gratitude practice and gratitude journaling. And I don't mean to, I grew up Roman Catholic and so I have plenty of experience of being guilted into, and I don't want to put this on anyone as some kind of religious guilt trip or anything like that.

I just, it is freedom for me. I bought this little Christian gratitude journal and it's incredibly simple. I can do it in five minutes, I can do it in 20 minutes, I can do it in three minutes, but I basically, I write down one thing that I'm grateful for. And this particular journal has a little scripture and I just read the scripture and I just write down a truth, a biblical truth, and then finally someone that I could pray for or serve. And oftentimes, you know, that person is not even someone who's locally very close to me and they're far away.

Peter, a couple weeks ago you were that person, I never told you about that. So starting a gratitude practice is incredibly helpful to get that soulish rest, because it'll help to kind of change our perspectives. Well put. Well, well said, and it's, the more you start expressing gratitude, and it's intentional by the way, it's not about feeling differently, it's about just being intentional on your gratitude and meaning it, it does redirect your mind.

We're talking with my friend John Paredes in Connecticut, we're talking with my co-host John Butler in Nashville, and Ed in Dallas is saying, hey, let's go to a break real quick. This is Hope for the Caregiver. We are thrilled to have you with us along on this journey.

Hopeforthecaregiver.com will be right back. Have you ever struggled to trust God when lousy things happen to you? I'm Gracie Rosenberger, and in 1983, I experienced a horrific car accident leading to 80 surgeries and both legs amputated. I questioned why God allowed something so brutal to happen to me, but over time, my questions changed, and I discovered courage to trust God. That understanding, along with an appreciation for quality prosthetic limbs, led me to establish Standing with Hope. For more than a dozen years, we've been working with the government of Ghana and West Africa, equipping and training local workers to build and maintain quality prosthetic limbs for their own people.

On a regular basis, we purchase and ship equipment and supplies, and with the help of inmates in a Tennessee prison, we also recycle parts from donated limbs. All of this is to point others to Christ, the source of my hope and strength. Please visit standingwithhope.com to learn more and participate in lifting others up. That's standingwithhope.com. I'm Gracie, and I am standing with hope. Welcome back to Hope for the Caregiver.

I am Peter Rosenberger. I love that with Gracie and Russ Taft on her records. Oh, I knew that about that.

Yeah, isn't that great? All right, to wrap this up, because we are in the season of Thanksgiving. On October 1963, October, I think it's October 2nd or 3rd, in 1963, Lincoln established a National Day of Thanksgiving to be in November. I think you mean 1863, is that correct? I'm sorry, 1863, sorry.

I haven't had a lot of sleep, John. But it's 1863. Now, we're in the middle of the Civil War. More American lives were lost in the Civil War than they were in World War I, World War II, Vietnam, Korea.

No, we're still in the middle of the Civil War, a different kind of Civil War. But in the midst of clearly the greatest calamity to ever face our nation, that's when a National Day of Thanksgiving was established. And so the lesson learned from that is we don't have to have everything going our way in order to be grateful and express that Thanksgiving.

And we have a lot to be thankful for. And a friend of mine told me this, and we've said this on the show many times, when your mind is racing at 100 miles an hour, just take the alphabet. First letter, every letter, just come up with something that starts with that letter and be grateful for it, express thanks for it. And when you're doing this repetitively, and it feels kind of the first couple times you do it or whatever, but the thousandth time you do it, you know, it becomes a part of who you are and it helps settle your soul down. It's very hard to be taught when you are grateful, consistently grateful.

Yeah, deliberately so. And there is a reason why we have mantras or prayers or practices of some kinds where we get into the habit of doing something and being mindful about it. It can really just lower that blood pressure, calm you down a little bit, or, you know, it's this repetitive thing that you don't have to really think about the process of it.

And it becomes this habit, this little bit of comfort in which you can participate, and a very predictable one. By the way, it costs nothing. Yeah, yeah, it costs nothing. It costs nothing to say thank you or to express gratitude. And I remember a dear friend of mine told me one time, because I always felt kind of weird when people would give me a compliment, you know, I loved your playing the other day at church or your show has really, and I would try to diffuse it with some kind of self-deprecating humor. And he said, cut that out, just say thank you.

Don't kneecap your statements is a word that I heard, you know. So, John, JP, take us into a place of gratitude, you know, how that shaped your life. As you started doing these things, what did you notice as you started writing that gratitude journal and things such as that? Yeah, the big monsters got smaller and smaller. The things you dread and the stresses and the fears, they just seem to shrink a little bit. And when you think and you kind of reprogram, I guess, your mind, you start looking at positive things, the things that you're grateful for, the things that you're blessed with, the problems are still there. You know, this isn't some kind of Pollyanna thing where you stick your head in the sand and don't acknowledge the problems there.

But the problems, they have less venom. The things you seem to slow down a little bit. I remember my sister and I had a wonderful thing. Peter, you alluded to it earlier. You know, sometimes God calms the storm and sometimes God calms his child.

And I remember I read that. And given that, I would always want God to calm me down in the storm. Because I think, and this isn't bravado or anything, but I would rather handle that storm in a calm, because we're going to have those storms. And if I'm in a calm state and I'm finding a good place and I'm thinking clearly and I'm rested and whatever, I can take that on and I can find the right resources. I can call the right person or get the right help or whatever. But if we're a mess, it doesn't matter if the storm has come.

What did that achieve? I'd rather fight a storm than a calm stream. And I think gratitude can get you there and gratitude can get you to look at that storm differently.

And there's so many benefits to it. Raging storms make better sailors. And, you know, one of the things I said this morning at our worship service is learning to be thankful for unpleasant things. Or, you know, in the pleasant things. Scripture says be thankful in all things. And I go back to one of my favorite stories was Betsy Ten Boon in the Holocaust telling her sister, Corey, to be thankful for the fleas in their hut that all these women stayed in.

And Corey Ten Boon just absolutely just snarled back. She hated it. She was incredulous to be thankful for fleas.

But it was the fleas that kept the German guards from molesting the women. And, you know, you just learn to be thankful for even small things. Things that you wouldn't think about. But when you cultivate that, okay, I'm going to be thankful in this place. And trust that I have a God that is loving me and caring for me and going to see me through this and equip me to do better through it or take me home, whatever.

But it's going to still go in a place that he wants it to go, however painful I may think it may be. And these are hard things, but they're important things for us as caregivers to understand that, you know, we're not being punished. This is not the wrath of God being poured out on you because you're taking care of somebody who had a stroke or somebody with disabilities or whatever. But this is an opportunity for you to go deeper and deeper, see his faithfulness and his grace and his mercy in ways that you would not normally experience. And to learn to, as we often say on the show, the goal is not to feel better. The goal is to be better. And if we are spending all of our time trying to feel better, you know, what kind of life is that? So last words, JP and then John. Last word.

We've got one minute, JP and then John. Yeah, well, we're actually doing a series on mental health at our church. And we had a clinical psychologist who came in today and said something very similar to what you just said. You know, she talked about something that we can do here on earth that we'll never be able to do in heaven and beyond is thank God and express gratitude when we're in the middle of a very difficult situation, because when we're in heaven, there's going to be a difficulty. So the fact that we can do that now is just an incredible thing and is very, very empowering. And and I think it unlocks all kinds of blessings from heaven. And it certainly unlocks all kinds of stress and all kinds of negative things out of our lives. And so that's very it's amazing that she had she had said that and I grabbed on to that and it dovetails nicely with what you just said there.

Butler, 30 seconds. Well, I just wanted to emphasize that I'm not interested in making I'm not interested in God making my life easy, but I am interested and strong enough to get to get to it. You know, I thought, yeah, if everybody gets if it's all handed to you, then come on. You know, you never get any better at it. And I just everybody go read the book. Guys, just go read Joe. You know, you'll be fine.

Go read Joe. Well said, Butler. But as it says in Dallas on the screen here, Butler for the win, Butler for the win. But hey, listen, both of you guys are dear friends to me. I am grateful for both of you.

And sleep and rest are two different things. And I hope that we've helped point some caregivers in physical directions and a soul healing direction as well with rest. This is Peter Rosenberg. There's hope for the caregiver. Please, please share this episode with somebody you love who's going through some things. It's all at Hope for the caregiver dot com.

We'll see you next week. Hey, this is John Butler, producer of Hope for the caregiver. And I have learned something that you probably all know that Gracie, his wife lost her legs many, many years ago and started a prosthetic limb outreach ministry called Standing with Hope.

And recently they ended up with a rather unique and unexpected partner. Peter had a conversation with Gracie and take a listen. Gracie, when you envision doing a prosthetic limb outreach, did you ever think that inmates would help you do that?

Not in a million years. When you go to the facility run by CoreCivic over in Nashville, and you see the faces of these inmates that are working on prosthetic limbs that you have helped collect from all over the country that you put out the plea for. And they're disassembling. You see all these legs like what you have your own prosthetic and arms and arms. When you see all this, what does that do to you? Makes me cry because I see the smiles on their faces. And I know I know what it is to be locked someplace where you can't get out without somebody else allowing you to get out. Of course, being in the hospital so much and so long.

And so these men are so glad that they get to be doing, as one band said, something good finally with my hands. Did you know before you became an amputee that parts of prosthetic limbs could be recycled? No, I had no idea. You know, I thought of peg leg. I thought of wooden legs. I never thought of titanium and carbon legs and flex feet and sea legs and all that.

I never thought about that. As you watch these inmates participate in something like this, knowing that they're helping other people now walk, they're providing the means for these supplies to get over there, what does that do to you just on a heart level? I wish I could explain to the world what I see in there. And I wish that I could be able to go and say, this guy right here, he needs to go to Africa with us. I never not feel that way.

Every time, you know, you always make me have to leave, I don't want to leave them. I feel like I'm at home with them and I feel like that we have a common bond that I would have never expected that only God could put together. Now that you've had an experience with it, what do you think of the faith-based programs that CoreCivic offers?

I think they're just absolutely awesome. And I think every prison out there should have faith-based programs like this because the return rate of the men that are involved in this particular faith-based program and the other ones like it, that I know about this one, is just an amazingly low rate compared to those who don't have them. And I think that that says so much.

That doesn't have anything to do with me. It just has something to do with God using somebody broken to help other broken people. If people want to donate a used prosthetic limb, whether from a loved one who passed away or, you know, somebody who outgrew them, donated some of your own for them to do, how do they do that? Oh, please go to standingwithhope.com slash recycle. Standingwithhope.com slash recycle. Thanks, Gracie.

Whisper: medium.en / 2024-01-25 00:35:57 / 2024-01-25 00:58:42 / 23