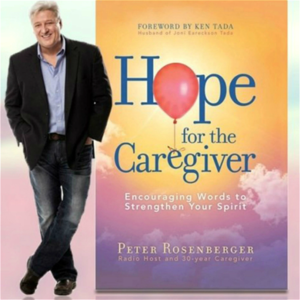

Hey, this is Larry the Cable Guy. You are listening to Hope for the Caregiver with Peter Stay strong and healthy as you take care of someone who is not. How are you feeling? How are you doing? How you holding up?

What's going on with you? 877-655-6755. If you want to call in live for our streaming audience, we have a streaming audience on our Facebook pages of you can go to Hope for the caregiver or standing with hope or Hope for the caregiver group that you can join. And we'd love to have you be a part of the show 877-655-6755. Otherwise, you're stuck with just me and himself the man you know, And knowing you love him, you've seen his press release, he is John Butler, the Count of Mighty Disco, everyone.

What is this? Yes. Good evening, good morning, good afternoon, good whenever and wherever it is you find yourself. I, of course, am John Butler, and I'm here with you, Roosevelt.

That was my live intro for you. By the way, just a curious note. You may find this interesting. One of the rules in music, particularly when you're scoring music and composing and so forth, is you don't do parallel fifths. So here's an example of a parallel fifth.

You don't want to do that when you're harmonizing, like with hymns and things such as that, which is the foundation of a lot of Western music, is your hymn structure. But Henry Mancini, who did that for the Pink Panther, that is all parallel fifths. Oh wow, okay. And he just purposely broke the rule and made it iconic. Absolutely.

Well, nothing else sounds like it. Well, that's true. And so I thought that was kind of cool, that he breaks the rule and makes it iconic. So rules are meant to be broken, and that's a pretty good topic for us to take as caregivers, you know, because I think we get locked into rules. Well, and you have to know the rules before you break them and know why they are the rules. And you have to break them with intent as opposed to accidentally.

Exactly. And that is a good lesson for us as caregivers, is know that there are some things, you know, it's okay for us to adjust and do. And I think when you start out as a caregiver, you put these unreasonable expectations on yourself, and then where does it go from there? And then you have to go back and say, okay, wait a minute, maybe I wasn't supposed to do it this way. Maybe it's okay if I do it this way. But that takes a little bit of seasoning, and it takes a little bit of permission to do that. And if you can't give it to yourself internally, and most of us can't, then we're going to need that permission externally from someone, whether it's a counselor support group, fellow caregiver who's been down this road a while, you know, whomever, wherever you can find that. But don't sit there and lock yourself into your own way of thinking.

Well, I read an interesting, it wasn't even a story, it was just a little, you know, somebody had posted this on Facebook or something like that. And you know, they were talking about a session they were having with their therapist, where they said, you know, the dishes pile up on me, and I can't, you know, it really just the dishes, if I can get the dishes taken care of, that would make my life just run a lot smoother. And I just can't ever bring myself to do them. And the therapist was like, well, I mean, you got paper plates, right? And they're like, yeah, but why, you know, you can't use paper plates all the time.

Why not? Is it a... China, baby. China. Yeah.

Dixie cups. And it feels like, you know, it's like, well, you know, mom would be really upset if she started doing well. She's not living with you right now. So just go ahead and use the paper plates and it'll make your life better. And they needed that permission from their therapist. Isn't it odd? Yeah. That we back ourselves into those kinds of corners and it's self-inflicted. Yeah. And it goes, well, habits are really hard to break, you know, and very, very difficult to build.

I think Chicago did that song, you're a heart, habit you break. I was the one that was supposed to come up with trivia. But do you have a dad joke? Well, we'd like to start off with a dad joke first. I had a pun about paper, but it was just terrible, you know? Do you have crickets? Do you have something you can put in there to let people know that that was truly, that was truly painful?

Arid. That was really bad. Pass the butter, I smell corn kind of thing. Do you have something better, John? I do. I do. You know why the ocean is salty? No, I do not know why the ocean is salty, John. Yeah.

Well, it's because the land never waves back. Again. Okay.

Just crickets. You know, even as far as dad jokes go, it's a good thing that we have a prosthetic limb ministry because there's a lot of lame material here. Oh. Oh, there you go.

Well, look, I'm just looking for a leg to stand on. Oh, by the way, I was doing the show yesterday, the broadcast show. We did the broadcast show on Saturday's live and it's really more color driven. This show is designed for John and I to unpack some ideas and we'll have special guests on and so forth.

But the live show is every Saturday morning, 8 a.m. Eastern, but I had a lady call in that she was taking care of somebody who had their toe amputated. And I did, after I expressed concern and so forth, we talked about it, I did have to weave in the tow truck conversation because I, you know, I mean when your wife's a double amputee, you kind of, you've heard all of these. I mean, she's been an amputee now for many, many years, so over 30 years.

And 30 years this year, actually 30 years this year. And so it's one of those things that she realized that this is so not a part of her identity is her self-worth and that gives permission. That brings me back to what we're talking about is giving ourselves permission to feel, believe, act, do things that maybe we've pigeonholed ourselves into doing. And that becomes the case I've found with a lot of caregivers, it was that way with me. And I can't do that, I'm supposed to do this.

And that goes back to the fog of caregivers that I talk about quite a bit, the fear, obligation and guilt. And I'd like to spend some time with that obligation today. It's that obligation of, and here's how you know that you're dealing with it. I have to, I'm supposed to, I must. You know, and like we talked about with the song for John's spectacular intro, when I did parallel fifths, and you're not supposed to do that in music, that is a rule, don't do parallel fifths.

And then here, Henry Mancini, one of the greatest composers around, been film composers and so forth, came up with this way of turning parallel fifths, a rule that you don't do, into a iconic theme song for the Pink Panther. And so that I'm supposed to gets a lot of people in trouble. You ever been beleaguered? By the way, I'd use that word for the big board, John. Beleaguered?

Yeah, I was going to say that's from the, that's about six and a half dollars worth. Have you ever been beleaguered by supposed to? Oh, I mean, besides, you know, paying rent and stuff like that. But you know, we all have. And I think about it with what I've had to go through with the kids this past year.

And because they're in distance learning, they're at home with me all the time. And that has created this. You know, when you start doing it, you're like, okay, I need to, I must have this exacting schedule and getting up and doing everything at exactly the same time so that they have some sense of normality. And let's be honest, normality went out the window a long time ago. We're several exits past normal.

Yeah, that ship has sailed. But making sure that, okay, giving myself the opportunity to break that schedule if I see an opportunity for like, oh, you know, let's go out to the field and throw a ball or a Frisbee around or something like that. When we've got, because we happen to have time, you guys are done with your whatever, it doesn't have to be exactly at 2.30 or something.

But as long as you get the stuff done, it sometimes doesn't matter that it's, you know, maybe a little bit of a wonky day or something like that and not beat myself up over missing, you know, the 12 o'clock window for whatever. Well, the school system in general is set out as an institution. And it is set out to provide a structure to train in a uniform manner the most kids possible.

Train and educate. And I've used that word educate sometimes a little bit guardedly, because education can take on many different forms. But I go back to historically, a lot of times, most of the education went on in the family.

I can think of several cases with that. Susanna Wesley, who had like, I don't know, a passel of children, Jonathan, she had 19, she and her husband had 19 children. Not all of them lived because back in the 1700s, you know, the infant mortality rate, but she did have, somebody used to come up to me and say, did your parents have any children that lived?

You know, that's an old joke. But it's, no, but she trained her children at home. And she made sure they had an education. And two of them grew up to be two of the most famous ministers in history.

One was Charles Wesley, her son, and the other was John Wesley, just a mate who was the founder of the Methodist Church. But he was educated at home by his mother. And that's the way they did it. And so I don't think that we have to, I think we've grown up in a situation where the kids have to go to school, do this, we go to eight to four, whatever. But that may not be the best way that your children learned.

That may not be the best way to do it. And even if it's the way we have to do it because of societal functions, doesn't mean that we're locked into that education. And I grew up in an environment where we sat around the meal table. Do you guys have a lot of meals around the table together? That is one of the things that, you know, while I do occasionally give myself permission to, like, hey, let's, you know, let's have a less formal thing. But I really do try to have a dinner around the table every night. I also love to cook.

So, you know, that kind of helps. I grew up in that. And I have four brothers and a sister. And we had incredibly lively conversations around the table. My dad was a minister, but he was also captain of the Navy. And so current events, the news, things such as that, those were important topics of conversation. Now, with four brothers, with five boys, you know, things would devolve quickly sometimes.

And, you know, rather spirited, let's say, dad would bring out the captain voice and say, boys, you know, that kind of thing. But when I was, you know, when my children were in school, we made it a practice to sit around the table and have meals where we would talk about the things of the world. I would read to them and so forth.

And I think that we learned that they learned in a different way, maybe then maybe some of their plasmids. Because I noticed that a lot of families did not sit around the table and eat dinner. And they could trace that back, by the way, you could, there are statistics that prove a difference in children who sit around the meal table as a family and eat. There's behaviors of learning, of, you know, adjustment to society and all those kinds of things. A lot of it has to do with the family meal time.

And that's however you define it. I mean, sometimes, you know, we would substitute our table for the table at Mazatlan there in Brentwood, you know, where I spent a lot of time there. And I love that.

It's a very nice endorsement, by the way, if they would like to sponsor us, I will happily take some gift cards. We raised our kids over there, I think sometimes. But you know, the Waffle House, you know, but you go and you break bread as a family and then that becomes an opportunity for robust conversations that are not about silliness, but about education. Do you find as a parent that you are weaving in the lessons of the school year when you do some of these, let's just go out to the field or whatever? Yeah. Well, one of the things where the great thing about the divide, like the ages my kids are right now, they're 13 and about to turn nine and we've got to wrap this part up. But like Kerrigan is 13 and her history lessons are about things that I truly am interested in like the Crusades or the Silk Road or something like that. So I get to, you know, lay that on to my son as well, Malcolm.

Are you going back to school yourself now because of this? Oh, it's fun. It's fun. Yeah. A little bit, a little bit. Well, I truly like that stuff.

So it's a treat. Well, we're talking about... We'll finish it up after the break. Well, we will.

We're going to take a quick break. We're talking about obligation and the way it's supposed to be done. It has to be done. We're supposed to. We should. And I'm saying, no, it's okay to bend the rules. Let's know what the rules are and then let's bend them and make it work for us as caregivers. We'll be right back. This is Peter Roseberry. This is hope for the caregiver.

Don't go away. Have you ever struggled to trust God when lousy things happen to you? I'm Gracie Rosenberger and in 1983 I experienced a horrific car accident leading to 80 surgeries and both legs amputated.

I questioned why God allowed something so brutal to happen to me, but over time my questions changed and I discovered courage to trust God. That understanding, along with an appreciation for quality prosthetic limbs, led me to establish Standing with Hope. For more than a dozen years we've been working with the government of Ghana and West Africa, equipping and training local workers to build and maintain quality prosthetic limbs for their own people.

On a regular basis we purchase and ship equipment and supplies, and with the help of inmates in a Tennessee prison we also recycle parts from donated limbs. All of this is to point others to Christ, the source of my hope and strength. Please visit standingwithhope.com to learn more and participate in lifting others up. That's standingwithhope.com.

I'm Gracie and I am standing with hope. 24-7 emergency support, increasing safety, reducing isolation. These things are more important than ever as we deal with the challenges of COVID-19. How about your vulnerable loved ones?

We can't always check on them or be there in ways we'd like. That's why there's Constant Companion, seamlessly weaving technology and personal attention to help push back against the isolation while addressing the critical safety issues of our vulnerable loved ones and their caregivers. Constant Companion is the solution for families today, staying connected, staying safe.

It's smart, easy and incredibly affordable. Go to www.mycompanion247.com today. That's mycompanion247.com. Connection and independence for you and those you care about.

Mycompanion247.com. I'm alive, lift up my voice. Love the chaos and the noise. It's all my hope amidst the pain. I shout this song against the rain. Rejoice, evermore, evermore. Welcome back to Hope for the Caregiver.

This is Peter Rosenberger. This is the nation's number one show for you as a family caregiver. How are you feeling? How are you doing?

How are you holding up? We're talking today about obligation. It's part of what I call the fog of caregivers, fear, obligation and guilt, and every so often I need to review this for myself because we get into these places where we're somehow thinking that we have to, we must, we should, and we're staying with conventional things and conventional things don't always work.

Conventional things often don't work when you're a caregiver. But it's important to learn what the convention is so that you can deliberately work against that in a positive way, not in a destructive way, not in a haphazard way where you're feeling guilty or anything like that so that you can feel a little bit more in control of what you're doing and realize, oh, okay, I'm doing this and this works. And so it's like, for example, now I did a musical object lesson with John's intro today and I think I'm going to do that for you, John, as we move forward. I'm just going to keep coming up with great musical intros for you that I just play on. There you go. Yeah, just on the thing. We'll have to bring my keyboard in here and do a dueling pianist thing. Well, but it was the thing from the Pink Panther where Henry Mancini, the composer, is using parallel fifths, which is a known as one of the first things you learn in composition in theory and so forth that you don't do parallel fifth.

And yet he did it and made it iconic. And so what are some things as a caregiver that you're having to realize that maybe you pigeonholed yourself in and said, okay, I have to do it this way. I must do it this way. And for me, I had to get to the point where I was beating my head against the wall in a situation where I was feeling all this pressure that I must be so in command of Gracie's chart, for example, that I was the guy that knew all this stuff.

I was trying to keep up. And this point was driven home to me when I watched my father do this with my mother. A couple of years ago, my mother underwent some surgery and she was pretty ill. She was in ICU and it was pretty dicey.

She had congestive heart failure. And my father has a terminal degree in his field. He's a minister. He has a doctorate.

He was a captain in the Navy, which is basically the equivalent of full colonel in the army. I said, oh, six. This is an educated man, a very smart and wise man. And I watched him struggling to keep up with the doctors and trying to keep his, you know, keep engaged. And I could see that he was faltering. In all fairness, he was a little over 80 at that time.

He still is over 80, but he's further away from 80 now. But he was struggling and I watched him and I pulled him aside and I said very gently to him, I said, Dad, I've got over 30 years head start on you on this and I'm a pretty capable fellow, but I can't keep up with this stuff. And I realized that I don't have to.

That's not my job. I said, you went to divinity school, not medical school. Do something divine. And he looked at me kind of funny and he realized that I went back and I saw him later in the lobby and he was just, he was reading his Bible. He was sitting there being very contemplative. And then he, you know, when he spent time with mom, he would be in there and he would be her husband and pray with her, read scripture to her and pastor her. But he didn't try to learn all the medical stuff.

But it took me, his son and his junior by 30 something years, 30 years, to give him permission to back away that he did not have to keep up with the doctors. And I thought, boy, that's a teachable moment. And that's part of why I do this show is because I saw that the value in being able to come alongside people and say, you know, you really don't, you're not required to do it this way. There's no rule book says this is it, you know?

And so anyway, your thoughts, John, I can see that you're bursting with enthusiasm to speak. Well, no, but yeah, again, the giving of permission, even from, now your father respects you and respects your opinion in these matters. So you had a really good relationship already, but it's still, oh, it's, you know, this young kid that, you know, it's just my kid telling me that I don't have to do this.

But, you know, to get permission for that is, again, that is a difficult thing to humbling, you know, and to realize that we don't have to do all these things. But one thing I do, that I've been thinking about this through this whole conversation is, you know, we talk about the obligations we place on ourselves and we talk about obligations being a quick path to resentment. And I think resenting yourself might be the worst kind. I have found it to be so. Because when you resent other people, at least you don't have to look at them every day, but with yourself. Yeah, you can just walk away, you know. But one of the reasons I put this in other terms, so like the music thing, for example.

It's because I think it helps us disassociate from the emotional pull that we have as caregivers. So I go back to Henry Mancini and we were in composition, when I was studying composition formally in college, music composition, you know, and even before that in theory classes, I've been taking musical theory since I was a teenager. And so it was drilled into our heads. You don't do parallel fifths.

You just don't do it. But if Henry Mancini had subscribed to that rigidly, we would never hear the theme from the Pink Panther. I mean, think about it, which has brought, you know, immediate a smile to anybody's face who hears it.

You immediately start smiling. And I thought all those smiles would have been forever gone had this composer not thrown the rule book out the window once he understood it and said, no, I'm going to do something different here and I'm going to make it work. And I thought, you know, as caregivers, can we learn from that? Can we bend the rules? Can we alter the way we look at this?

And one of the biggest things I have found for me is when I came to understand that my wife has a savior and I'm not that savior. You know, and for those in recovery programs, they would say things like your loved one has a higher power. You're not that higher power. You know, and that's a rule bender for caregivers because we feel like it's all up to me. It's all up to us. And then we feel obligated to meet that incredibly unattainable standard. I mean, incredibly unattainable standard. You cannot do this.

And this is 35 years talking. You can't. Trust me. You just can't do it. It's unsustainable. It is unattainable. Do you got another one that rhymes with that, John? Oh, um, unsustainable, unattainable, and come on, give me your best Jackson Jackson. It's unsustainable.

It's unattainable and the song is unrefrainable. Nice. Nice. There you go. All right. You win this round. Rosenberger. Sorry.

I can't believe I just took all that into imitation of Jesse Jackson. This is Hope for the Caregiver. This is Peter Rosenberger. This is the show for you as caregivers. We're here with John Butler, the man with the plan, and we're glad that you're with us.

Don't go away. We've got more to go, and you can always be a part 877-655-6755, or you can message us on our Facebook live streaming from Hope for the Caregiver on our Facebook page. Healthy caregivers make better caregivers.

Let's get healthier together. Okay? Thank you. This is John Butler, and I produce Hope for the Caregiver with Peter Rosenberger. Some of you know the remarkable story of Peter's wife, Gracie, and recently Peter talked to Gracie about all the wonderful things that have emerged from her difficult journey. Take a listen. Gracie, when you envisioned doing a prosthetic limb outreach, did you ever think that inmates would help you do that?

Not in a million years. When you go to the facility run by CoreCivic, and you see the faces of these inmates that are working on prosthetic limbs that you have helped collect from all over the country that you put out the plea for, and they're disassembling, you see all these legs, like what you have, your own prosthetic legs. And arms, too. And arms.

Everything. When you see all this, what does that do to you? Makes me cry, because I see the smiles on their faces, and I know, I know what it is to be locked someplace where you can't get out without somebody else allowing you to get out. Of course, being in the hospital so much and so long. And so, these men are so glad that they get to be doing, as one band said, something good finally with my hands. Did you know before you became an amputee that parts of prosthetic limbs could be recycled?

No. I had no idea. You know, I thought of peg leg, I thought of wooden legs, I never thought of titanium and carbon legs and flex feet and sea legs and all that. I never thought about that. As you watch these inmates participate in something like this, knowing that they're helping other people now walk, they're providing the means for these supplies to get over there, what does that do to you, just on a heart level? I wish I could explain to the world what I see in there. And I wish that I could be able to go and say, this guy right here, he needs to go to Africa with us. I never not feel that way.

Every time, you know, you always make me have to leave, I don't want to leave them. I feel like I'm at home with them and I feel like that we have a common bond that I would have never expected that only God could put together. Now that you've had an experience with it, what do you think of the faith-based programs that CoreCivic offers? I think they're just absolutely awesome and I think every prison out there should have faith-based programs like this because the return rate of the men that are involved in this particular faith-based program and the other ones like it, but I know about this one, is just an amazingly low rate compared to those who don't have them.

And I think that that says so much. That doesn't have anything to do with me, it just has something to do with God using somebody broken to help other broken people. If people want to donate a used prosthetic limbs, whether from a loved one who passed away or, you know, somebody who outgrew them, you've donated some of your own for them to do. How do they do that? Where do they find it? Oh, please go to standingwithhope.com slash recycle, standingwithhope.com slash recycle. Thanks, Gracie. One of our generous sponsors here at The Truth Network has come under fire.

Fire from the enemy. Fire for standing up for family values. Actually one of the biggest supporters of the movie Unplanned that talked about the horrors of abortion. Yes, it's Mike Lindell. You've heard me talk about his pillows for a long, long time and no doubt big business is responding to Mike Lindell and all this generosity for causes for the kingdom by trying to shut down his business. You can't buy his pillows at Kohl's anymore. You can't get them on Amazon or you can't get them at Costco.

They're attempting to close his business because he stood up for kingdom values. What a chance to respond, especially if you need a pillow. Oh, I've had mine now for years and years and years and still fluffs up as wonderful as ever. Queen size pillows are just $29.98. Be sure and use the promo code Truth or call 1-800-944-5396. That's 1-800-944-5396. Use the promo code Truth for values on any MyPillow product to support truth.

Whisper: medium.en / 2023-12-30 23:06:30 / 2023-12-30 23:18:50 / 12