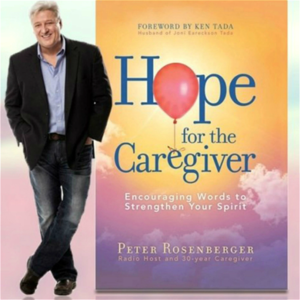

Welcome back to Hope for the Caregiver. This is Peter Rosenberg and this is the program for you as a family caregiver and we're so glad that you're with us. Hopeforthecaregiver.com.

Hopeforthecaregiver.com. I have the opportunity to meet some very interesting people along our journey and I'm always looking for ways to address a topic that affects so many of us as caregivers. And one of those is pain, chronic pain, trauma, physical pain, all the things that go on when you deal with the kind of issues that we deal with as caregivers. Most of you all know my wife had a horrible accident when she was 17 in 1983.

Her body is an orthopedic train wreck. And we've talked with a lot of pain doctors over the years. And in this last surgery she had, one of those came into her room and we got to talk a little bit. And I was so moved by the way he approached her pain and how he interacted with her. And I've dealt with a lot of pain specialists since I met my first one in 1990, in 1990.

So that ought to give you an idea of how far back I go with this. And this gentleman was just, it really was extraordinary to watch him work. And he had a whole bunch of residents in tow with him and they were all taking notes and they came into the room and we just started to have these amazing conversations.

And I watched how gentle and tender he was with Gracie and understanding, and yet he was just bubbling. He loves his work. And so I wanted to have him on the program. This is Dr. Roland Flores, and he is at the University of Colorado Medical Center. And he deals with, he's a professor, pain management, acute care. And so I wanted just to introduce him to you all and let's have a dialogue so that you can understand a little bit more about this journey. Some of you are just now stepping into the world of chronic pain.

And I want to give you as much information as you possibly can so that you can navigate this a little calmer. It is not just the loved one that is in pain. Pain is a part of your life. When you're dealing with a chronic pain patient, there are multiple things going on.

And if we don't prepare ourselves for it, if we don't educate ourselves, it's going to take us under. So Dr. Flores, thank you very much for taking the time with this. I really do appreciate it. Of course.

Very happy to be here, Peter. All right. Before we get too far down this road, I know this sounds very fundamental, very basic, but share with us the difference between acute pain and chronic pain and how pain management teams approach those two different types of pain.

Sure. So I think when I got started in this, gosh, now going on almost 15 years ago, there was a much kind of larger differentiation between chronic and acute pain. Chronic pain as it has been traditionally defined is a kind of a painful condition that goes on for six months or more. And acute pain falls into the category essentially of pretty much everything that is not that. The way I kind of go about it a little is that if you've been blown up, run over, stabbed, shot, had a difficult surgery, some kind of injury or surgical trauma, then my team, my acute pain team is who is called to help manage that type of thing.

I think what has happened in the last probably decade, maybe a little less is that, like I said, those lines have been blurred a little bit. And what my practice now, what I kind of see predominantly what I've tried to focus my attention on is acute pain in the chronic pain patient. Someone who had a painful condition, again, kind of before something happened to them, whether that's injury or surgery, and how those two things now interact with each other. And so that's kind of, from my point of view, what I specialize in, the way that we approach that is to kind of figure out kind of what happened to this patient initially, what is their chronic pain problem or chronic pain issue, how has that been managed long term, and then how this new traumatic event kind of fits into that whole picture. Well, that's what really impressed me is because when you came in, I've dealt with so many doctors that came in hot with Gracie and saw she's in pain. Okay, we just throw this brick of drugs at her to kind of get her pain, but not really understanding that this is a woman who's lived with pain now since Reagan's first term. And she's had to work out some of that in her own mind and her body and everything else.

And you can't just parachute into this without understanding that kind of history. And the way you approached this was what really touched my heart because I thought, okay, fine, here's somebody who speaks this language, who gets this. And you guys came with this multimodal approach, which I thought was so effective with her, recognizing that, okay, there's no way we can take all of this away from Gracie.

There's no way that we can fix this problem, but what we can do is better equip her to navigate through this. And I thought, man, this is something we need to talk about on the program. Let me ask you this. What would you like if you had your wishlist?

What would you like for every caregiver of a chronic pain patient to know? That's a big question. I understand.

It is a big question. If you had your wishlist on that, what would you like for them to know? You know, it's kind of a funny, when I think about that a little bit, the first thing that pops into my mind actually is that I need your help. It's almost impossible for me to help people in these situations without the help of their family and their friends and the kind of the people that know them best. So I really think when I kind of approach these situations, the thing I need most is for this to be kind of a team effort. And I realized a lot of times when I meet patients and I meet their families and their caregivers for the first time, this is an incredibly stressful situation. Something horrible has happened, again, some kind of horrible injury or a very difficult surgery, very difficult diagnoses, and so I'm meeting them at a very vulnerable time. Many of them have seen other pain management specialists, have a lot of other specialized care kind of working for them, but have some preconceived notions about kind of what I do, how I can approach their loved ones or the person they're taking care of. And I think one of the very important things is that there's a lot of stigma, I think, surrounding chronic pain and the management of chronic pain. And the thing I really need from caregivers and from the people who know these patients best is to really know everything that's happening or that has happened for this patient. The things that have worked, the things that haven't, the side effects of treatments, how they've dealt with certain situations psychologically and emotionally. And I think what I really want people to know is that I really want and need their help. It's impossible to best treat their loved ones if I don't know everything and the only way that I can know everything is for us to all work together.

This is so important. You're right, we're so stressed about this situation. And I remember so many times when I would just go into a panic trying to get Gracie out of pain or talk to the doctor, put pressure on her, do this and this and this. And I was just in a free fall state of panic because I'd never seen anybody in the kind of pain she was in. And so I didn't have any experience.

They didn't teach me this in music school. And so I had to slow my heart rate down a little bit and learn to speak a little bit more calmly and understand the process. We didn't get here overnight. We're not going to get out of this overnight. And we may not get out of it at all, but what we can do is get through it.

And walk through it without having a panic attack. And I appreciate that very much of doing that. And I wanted the people listening to the show to understand that it is okay to be involved in this. But we start off by having clarity of thought and being able to explain the patient history and all that kind of stuff. What are some pitfalls that you would like families of pain patients to avoid? Some real danger areas for them.

Sure. So I think the most difficult thing is when patients and their families come in with kind of preconceived notions, preconceived kind of a feeling of how things will have to go. I think that every patient is different.

Every patient kind of has their own idiosyncrasies in terms of managing their pain. And so oftentimes they come with an idea of how things have to be. Certain management strategies, certain ways that they're approached or when I'm talking to caregivers how their loved ones are approached. And I think what I would want people to know is that we have so many different ways of tackling the issues that their family member or their loved one is going through. That at least from the beginning kind of try to hear us out. Kind of trying to see if the ideas that we have kind of fit into the notions that they have about how they should be cared for or how their loved ones should be cared for.

And I think more often than not, what we find is that we actually are probably more on the same page about these things than those preconceived notions would allow. And so I think that's probably one of the biggest pitfalls in terms of management. I imagine I don't have to tell your listeners this, but the other part of this too, kind of the greatest pitfall of this, and we talk a lot about this in medical training, but this is a marathon. These things, the issues that the people you're caring for are going through, many of them are not going to be solved overnight.

They may not ever be solved. And so what we can hope for many times is to improve people's quality of life, to improve how they're recovering from a surgery or from a trauma. But that these things obviously are ongoing.

They are long-term months, weeks, months, and years, if not forever. And so you have to take care of yourself, and I imagine, like I said, you talk about this a lot, but you have to take care of yourself along the way of this marathon, otherwise you're just never going to be able to, you're not going to be able to do your best to help manage the care of your family member. And so to really not let kind of everything else go by the wayside as you're helping your family member or your loved one out, to make sure that you're, you know, self-care, that you are kind of managing your own life as well as you can. Otherwise, I don't know that you can help your loved one as much as you would like. Wise words. And this is the core message of this program, healthy caregivers make better caregivers.

It's just that simple. And so you can bear with me for one more segment here. We're going to go to a break in just a minute, but I wanted to address that issue because this is an issue I think that a lot of caregivers get tripped up in. That, okay, we're going to see to our own emotional, physical, financial, professional health after our loved one gets better or possibly even after they get worse.

But we cannot wait for them to get better or worse to deal with some of these realities. And I also want to address the impact of chronic pain that is not just localized in that patient, that it is part of every part of your life. If you're in relationship with a chronic pain patient, we're talking with Dr. Roland Flores. He is a professor in acute pain management, University of Colorado Medical Center, and he has my eternal gratitude. This is Peter Rosenberger.

We'll be right back. Welcome back to Hope for the Caregiver. This is Peter Rosenberger. This is the program for you as a family caregiver.

Hopeforthecaregiver.com. That is my wife with rust half on her CD, Resilient, and the man who has been instrumental in helping her get back to that place. She's going to get back to singing in the studio is on the phone with me today is Dr. Roland Flores. He's an acute pain specialist at the University of Colorado Medical Center, and he's no longer treating Gracie in that because she's slowly transitioning now to the chronic pain component of what she's going to be doing.

But we met right after her surgery, and I was fascinated by his approach, by his enthusiasm. This is a hard field. Pain management is no easy place to go to as a physician because you're around very difficult things all day long, and you can't solve a lot of these things. You can help them. You can equip them. You can fortify them.

You can ease them, but you can't solve it. You got to learn to work with very high stressful situations. And so I wanted to have this conversation with him today for your benefit so that you can hear from somebody who is at the top of his game of dealing with this very painful issue. Difficult, difficult things to talk about with patients and their families. And yet, okay, how do we deal with this?

Because as caregivers, this is our world. So Dr. Flores, I just want to jump right back into something that you were addressing before the break about caregivers learning to deal with this. And what discouraged me, and I've really been on a mission with this, is that for so many years, a lot of doctors threw so many opioids at Gracie trying to deal with her pain management. Turns out she didn't need as many as they gave her. She didn't need a fraction of that.

She needed a different approach, which we've been working on for some time now, but they threw all this. And during that time, and I feel prescriptions, this will horrify you, but I feel prescriptions of seven figures worth of prescription opioids with her over a period of time. And not one doctor, not one nurse, not one pharmacist ever said to me, hey, we're putting a lot of behavior-altering chemicals into your wife's body. You might want to think of getting some help for yourself.

And nobody ever said it, so I didn't know. And it caused me to go into a dark place as well. And so that's why I'm trying to introduce this concept as best as I can to listeners, to people, to fellow caregivers to help understand, okay, look, if you're treating somebody for chronic pain, and there are any kind of behavior-altering drugs, whether it's benzos, whether it's opioids, whatever, step back a little bit and seek out some places for yourself to get some help, some counseling, some support groups, recovery programs like Al-Anon or whatever. Wherever you find people who are wrestling with something they can't control and learning to live with it peacefully, that's a good place for you to go find some help. And are you seeing that with family members along your journey, that they're themselves so torqued up that they can't hardly function very well?

So it's a little difficult kind of to tease that out sometimes. Obviously, my attention is so focused on the patient. I think you kind of hinted at something that I think is really important, talking about kind of certain classes of medications and how they affect people psychologically and affect people emotionally. I think we have to really be cognizant of the fact that obviously people who are suffering from chronic pain and chronic debilitating pain have high incidence of depression and anxiety that is related to and associated with that pain and the suffering that's associated with that. And that sometimes these medications can complicate those issues.

Sometimes people had some of those kinds of issues before whatever caused their chronic pain. And so I think, no, I don't see it that often in terms of kind of how family members are helping themselves, but I do see kind of, and again, I only get a brief snapshot of this, but I see what appears to be complicated relationships. We all have complicated relationships with each other, but you see some of the conflict is maybe too strong of a term, but kind of the interactions between people who oftentimes are both suffering in different ways.

The patients are suffering because of injury and surgery and difficult diagnoses, and I think that caregivers are suffering from feelings of helplessness and hopelessness and watching their family members suffer, as you just explained, kind of in an almost unimaginable way. And I think that we, again, kind of do ourselves and I think of myself as a caregiver, but in a different kind of an emotionally different way. And we do ourselves as caregivers a disservice when we ignore kind of how these very difficult kind of relationships can be for us to handle. And I think that those things can manifest as pathologies in our own lives that are completely separate from what's going on with those that we're caring for. And I think, like I said, we ignore those problems to our detriment.

Indeed. And you mentioned something in the last block I want to also touch base on, we caregivers often feel unqualified to even have a conversation sometimes, we get very intimidated by the brain power that can come into our loved one's room. And it is, we don't speak the language, we're not scientists, we're just somebody who loves somebody who is hurt. And I have said for some time that we as caregivers need to recognize that we have what I call caregiver authority. I don't know the science of all the stuff that goes on with my wife, but I know her. And we can speak to that and we can provide a historical context to anybody who's treating her, particularly when it comes to chronic pain. And I want to encourage those who are out there right now to make note of that, that you have caregiver authority.

And it's okay to wield that in an appropriate way to say, look, here's what I've witnessed, here's what I've seen, here's what I've experienced, here's what I've watched her or him go through. And these are things that will be extremely helpful to your physician. I'm going to pivot just a second here, but can you, to this topic, can you talk about this new study that's out on the long-term cognitive effects of benzodiazepines and what we as caregivers may need to watch for on some of this stuff?

Or do you put a lot of stock into that? I don't know the study that you're talking about specifically, but I do think kind of the long-term, some of these kinds of medications, benzodiazepines, opioids, other classes of medications, they have effects that go beyond pain management. And sometimes we talk about ways that kind of in a technical way, we talk about it in an allostatic reset, but that, you know, patients who may take benzodiazepines for anxiety may find that later in their treatment that they have more anxiety. That patients who take opioids for pain management may find that later on they have more pain. And I think these are difficult kind of side effects of incredibly important and useful medications. And that we kind of long-term use of those medications may have effects that we are beginning to kind of see kind of that picture more and more in those patients. And we really do need to kind of watch out for the long-term cognitive effects of many classes of drugs. And we now even within anesthesiology talk about the long-term cognitive effects of anesthesia-type drugs on patients.

And so these are not without, you know, oftentimes many of those medications are used for the short-term management of certain conditions and that the side effects of their use for the long-term management may be kind of intolerable either to a patient or to those around them. And that those kind of those issues require a lot of exploration for both us and science. Well, I want to address one subject you pointed out just there, but we need to watch and revisit some of these things. And please understand this to my listeners here. Please understand that when you're dealing in this world, it's not a one and done kind of thing where, okay, we got this and this is the track. We're going to be this way.

And for decades and years, we'll just kind of maintain. These things need to be revisited when you're dealing with this kind of trauma or this kind of significant pain issues. They need to be revisited often and have those conversation of, okay, do we need to tweak this to move this or whatever? And this is where we as caregivers can come into play because we're observing this loved one all the time. And so I wanted to close up with this last question to you is what type of questions would you recommend that patients and caregivers have when they meet with their care team, their patient care team?

And this is we only got about a minute or so. But what's the main questions or something you might want to have them write down? Sure. So I think this is a very important part of this. But I think a lot of patients and a lot of caregivers, what they really want to know is what's the plan?

What are we going to do right now? If that works, what is going to be the next step and the next step and the next step? Because like I said, I think that there is a lot of people come in with preconceived most notions. They come in with, again, feelings of helplessness and hopelessness. And I think what many people want is a plan and kind of what the A, B and C is going to be.

And if those don't work, what the X, Y and Z is going to be. And a timetable for that plan. Kind of when to expect results, when to worry, when not to worry, to really get a feeling that the person who's helping them, the medical professional who's helping them has a plan, has an idea of where to go and has some options for them. The other thing that I think really helps a lot of people feel more comfortable in these situations, and I think both for caregivers and for patients, is who is going to be available to my loved one while they're here if they're having a real problem. If they're having a pain crisis, if they're having a psychological crisis, if they feel like they need help, and especially at kind of the strange hours of the day at night and on weekends and during holidays. Who is it who's going to be able to visit them, evaluate them, manage them, and what is the plan for that? I really think that when maybe we don't necessarily have all of the answers, but if we have a plan, we have options, we have possibilities, then some of that feeling of hopelessness, some of that feeling that no one has heard them and figured out kind of how to help manage them.

Maybe some of that anxiety can be a space for people, and I think that that's incredibly helpful. Well said, well said. We're out of time on this, and I want you to know how much I appreciate this. You really did me a solid on this one, so thank you for calling in. Dr. Roland Flores, University of Colorado Medical, and he has brought so much insight to me through this journey with Gracie, and I thank him for coming today, and I hope it's been as meaningful to you all as it has been to me. Dr. Flores, thank you. Thank you so much for having me, Peter. I appreciate it. This is Peter Rosenberger, hopeforthecaregiver.com.

We'll be right back. Some of you know the remarkable story of Peter's wife, Gracie, and recently Peter talked to Gracie about all the wonderful things that have emerged from her difficult journey. Take a listen. Gracie, when you envisioned doing a prosthetic limb outreach, did you ever think that inmates would help you do that?

Not in a million years. When you go to the facility run by CoreCivic and you see the faces of these inmates that are working on prosthetic limbs that you have helped collect from all over the country, that you put out the plea for, and they're disassembling. You see all these legs, like what you have, your own prosthetic legs, and arms. When you see all this, what does that do to you? Makes me cry, because I see the smiles on their faces, and I know what it is to be like someplace where you can't get out without somebody else allowing you to get out.

Of course, being in the hospital so much and so long. These men are so glad that they get to be doing, as one band said, something good filing with my hands. Did you know before you became an amputee that parts of prosthetic limbs could be recycled? No, I had no idea.

I thought of peg leg, I thought of wooden legs, I never thought of titanium and carbon legs and flex feet and sea legs and all that. I never thought about that. As you watch these inmates participate in something like this, knowing that they're helping other people now walk, they're providing the means for these supplies to get over there, what does that do to you, just on a heart level? I wish I could explain to the world what I see in there, and I wish that I could be able to go and say, this guy right here, he needs to go to Africa with us. I never not feel that way.

Every time, you know, you always make me have to leave, I don't want to leave them. I feel like I'm at home with them, and I feel like that we have a common bond that I would have never expected that only God could put together. Now that you've had an experience with it, what do you think of the faith-based programs that CoreCivic offers? I think they're just absolutely awesome, and I think every prison out there should have faith-based programs like this because the return rate of the men that are involved in this particular faith-based program and other ones like it, but I know about this one, is just an amazingly low rate. Compared to those who don't have them, and I think that that says so much. That doesn't have anything to do with me, it just has something to do with God using somebody broken to help other broken people. If people want to donate a used prosthetic limb, whether from a loved one who passed away, or somebody who outgrew them, you've donated some of your own. How do they do that? Oh, please go to standingwithhope.com slash recycle. Thanks, Gracie.

Whisper: medium.en / 2023-05-22 07:20:16 / 2023-05-22 07:31:16 / 11