This is Michael Carbone with the Truth Network. We're partnering with Bible League International on Open the Floodgates, Bibles for Africa.

In many parts of countries like Kenya, Ghana, Tanzania, and Mozambique, as many as 9 out of 10 Christians are denied God's word by corrupt governments, majority religions, and poverty and remoteness. $5 sends a Bible. $100 sends 20. $500 sends 100. Call 800-YES-WORD.

That's 800-937-9673. Thank you for caring. Peter Rosenberger.

He's Irish on his mother's side. Welcome to Hope to the Caregiver. This is Peter Rosenberger. This is the show for you and your family caregiver. How are you feeling? How are you doing?

What's going on with you? 65 million Americans serve as a family caregiver. Maybe you're one of them. Maybe you're the one that's up late at night doing laundry, cleaning up, paying bills, getting up early in the morning, and calling insurance companies, doctor's offices, pharmaceutical companies back and forth to all these places, going to the grocery store, preparing meals, cleaning the house, helping a loved one get a shower. You know, there's all kinds of things involved in being a family caregiver.

Maybe that's you, and if you are, then we are glad that you're with us. This is the show for you to equip you with things that I've learned over a lifetime of this. I'm in my 35th year and counting, and I've learned a few things the hard way to help you stay strong and healthy as you care for someone who is not, and if you want to be a part of the show, 877-655-6755. It's Mother's Day as we're doing this show, and I'm reminded of a woman who called the show to share her feelings. We were talking about the topic of guilt, and she let off with, I'm an only child, and I took care of my father who passed away recently, and now I care for my mother with Alzheimer's, and I feel guilty if I can't see my mother every day at the center.

If I don't make it over there, I feel guilty, and you can really hear it in her voice, and I asked her, I said, is she safe? Yes, she replied. Is she warm, clean, well fed?

Yes. Does she recognize you? Sometimes, she answered sadly. Does she recognize the passing of time?

Not really. If possible, what would she say to you right now? Sniffling a bit, she whispered, you know, she would tell me that she loves me and to live my life and to be successful, and I said, well, you've done all you can to honor both your mother and father and care for them.

Visiting every day is a self-imposed requirement. You're doing the best you can, and by your own statement, they would approve and release you of your guilt. Letting go of the guilt and mourning the loss, but I also asked her, bask in the love that your family shared, and the guilt that she was torturing herself with was that she couldn't show up every single day out of some sense of imposed duty upon herself, and by realizing that she's really done everything she can to make sure her mom is okay and her mom is safe and her mom is well taken care of, and this was before the COVID, and nowadays with COVID, they don't let you into a lot of facilities, and that compounds the guilt, but if you've done all that you can do to make sure your loved one is safe and cared for and properly, you know, whether you've had to hire people to do it or whether you're doing it yourself, then that's all you can do. The best you can do is the best you can do. Let go of the guilt and instead bask in that love that your family shared and knowing that you have done indeed your best, and that is today's monologue.

Guilt is a terrible taskmaster to us as caregivers, and one of the things that we deal with a lot on this show is to help fellow caregivers let go of those things and learn to live a calmer, healthier, and even a more joyful life while serving as a family caregiver. All right, speaking of more joyful life, here's a man who is so awesome. He served as the inspiration for the Prime Directive. He is John Butler, the Count of Mighty Disco.

John Butler, the Count of Mighty Disco, and he's so tall. Well, that is high praise and a wonderful jingle if I ever did hear one. How you doing, Peter?

I'm doing well. You know, it was Cinco de Mayo was this week, this past week. It was, it was, yes. Did you have something to eat that was Cinco de Mayo-esque? I did have a margarita. I made elk tacos, and I let it cook all day long in the crock pot, and it was quite delicious, I might say. Oh, I'm sure, yeah.

I had no complaints. With elk, you have to, yeah, do you have to, is it like real tough? I mean, I guess you treat it like venison, you know? No, it's not real tough, and it doesn't have a lot of fat in it.

Okay, interesting. So that's, you know, that's the good news. Most game does not, and it's a lot more leaner than, you know, corn-fed or grass-fed beef, but it's, it is, it is delicious, and we had a fine meal, and I cook a lot of elk up here. We got a freezer full of it.

My brother-in-law got one last year during hunting season, and he left a bunch of it up here. He said, now look, you guys eat this. Nobody else is gonna eat it, so yeah, and I was like, okay, yeah, so I make elk tacos, elk spaghetti, elk chili, elk stroganoff, you know, so I've been eating a lot of elk, but here's something. Oh yeah, you get one of them, and you're like set for it.

Yeah, that's the whole point, and you're not buying beef every week at the grocery store. All right, what do you call, given this same topic of last week being Cinco de Mayo, what do you call a really awesome dessert, John? Oh, what do I call a really awesome dessert? A cheesecake. I don't know. Fluntastic. Now you know how I feel when you tell these jokes, these dad jokes. Oh yeah, well hey, you know, you know what a, you know what a pirate's favorite instrument is? No.

It is the lute. Okay, well I was trying to be with a theme here with Cinco de Mayo, and also, before we get back, I want to get back into the monologue and talk to you about some things on this, but I also want to acknowledge a milestone for this week. It will be our eighth year completed together. Ah, eight years, what do you know? Do you remember when we first started back in May of 2013?

I mean, I really try not to, but. It was, that was our first foray together in radio, and I'd been on the air about eight months prior to that, and then connected up with you, and it was just, you've been a tremendous teacher through this and mentor. You know, I came convinced and understanding the message of what I wanted to do and why I wanted to do it, but to be able to do this in this medium, you have been a tremendous help, so thank you for that, and happy eight year anniversary to our show. Oh, back at you.

Thank you, Peter. All right, let's go back to this opening topic of guilt, and actually I want to throw out a sentence to you, and I'd like to hear your thoughts on this, and it is directly related to what we talked about. When pragmatism collides with an emotional promise, now this is always in the context of the caregivers, not a covenant relationship in marriage of emotional promise and pragmatism. It's in the relationship with the caregiver, because a lot of people, and I'm finding this over and over, I heard this even last night, they're making deathbed promises to a loved one that they're going to do such and such for the surviving members, and pragmatically, that is just not feasible at times. Sometimes it can be done, but for the most part, it cannot be, at least the way it's envisioned, and they're doing this for a promise that was made 10, 15, 20, 30, 40 years ago, and all of a sudden they're berating themselves without mercy to live up to a promise they made.

What are your thoughts on that? Well, those promises, oh wow. Well, what I want to do is I want to give the emotion and the event that spawned this, the appropriate amount of reverence that it deserves. Making a promise to somebody when their days or hours or minutes away from death is sometimes a very good thing. If it's something like, hey, we'll have spaghetti dinner at least once a month or something like that, that's fine. Obviously, this is not that sort of thing, but there's a lot of stuff that happens between the time, if it's like 10, 20 years ago especially, there's a lot of things that happen that the loved one to whom the promise was made is not available to witness, to see all that. I need more of an example, I guess, to speak.

Well, in this particular case, yeah, go ahead. This woman, not the woman I was referring to in the monologue, but this other woman, I heard this even last night, made a promise to her mother that she would take care of her brother, but the brother situation has deteriorated significantly to the point where it's crippling this woman, but she's white knuckling it all the way through it. That is really rough, and what I would say in situations like that, well, there's always all those clauses that are unspoken when you're making a promise like that. You say, I will take care of my brother to the best of my ability or as long as possible, because if we cannot save everyone, we are physically unable to do so.

That's like saying, well, I'm going to go out and I'm going to be the first person on Mars or something like that. There's a limited amount of ability that we have there, and everybody knows that. Whether they speak in the moment to themselves or others, and that guilt can be difficult to get over, and it's not going to happen immediately, but I would try to... We talk about forgiveness and forgiveness being taking your hands off of somebody else's throat.

Well, we need to forgive ourselves a lot too, and that's what guilt is, and being able to give ourselves that grace. In this particular case, this woman, this was all self-imposed. Oh yeah. There's nobody forcing this.

Why? But the situation, the landscape changes. Yeah, and there's two people in that decision too. Like she said, I'm going to take care of my brother. Well, the brother might not want to be taken care of. Or his needs exceed her abilities. Correct.

And when that happens, what does that look like? And so what I hope on this show that we're able to do is have a meaningful dialogue and discourse about this so that we can at least put it out and give it some air, the conversations of air, because a lot of these conversations are kept in the exclusive world of internal conversations. When you're late at night and laying in bed and you're having this replay of these tapes over and over and over and over and over, this is what I got to do. This is what I got to do.

This is what I said I was going to do. Did you ever see Lonesome Dove? I did not know.

Lonesome Dove is one of my favorite westerns and Captain Call and Augustus McCurry played by Tommy Lee Jones and Robert Duvall. And they're both long-time friends, Texas Rangers. And I won't give anything away. Yes, I will. But this is a spoiler. So if you haven't watched it and you think you're going to, just deal with it. I'm going to spoil it. But towards the end of the movie, Robert Duvall's character, Augustus McCray, gets injured. He ends up losing a leg, but not before the poison sets in. And he's going to, he really needed to lose both of his legs in order to do it, but he wouldn't let him amputate the other leg. And the poison's taken over and he's going to die.

It's inevitable. And these are lifelong friends. And he looks at Tommy Lee Jones's character, Captain Call, who's stubborn and hard-headed and stuff.

Yeah. And he said, I'm going to give you one last gift. And he wants him to take his body back. They're in Montana. They drove a cattle all the way to Montana.

That's why I like this movie because I'm out here in Montana. And he said, I want you to excuse me, take my body back to this place near San Antonio, this little pecan orchard, which was special to him. And he said, I want you to bury it there.

And it's 2000 miles. And Tommy Lee Jones agrees to do this. And he takes it back there and he, he's bedraggled, he's beat up, he's bloodied and everything else, but he finally buries his body. He says, well, there you are. I guess that'll teach me to be more careful. What I promise next time, you know, and, and I think that speaks to me as a caregiver, you know, because there you are, I guess that'll teach me to be more careful. So I'd say to my fellow caregivers, let's put it in context of what's really going on.

The landscape does change. We're going to talk about this some more. This is hope for the caregiver.

This is Peter Rosenberger. This is the show for you as a family caregiver. Healthy caregivers make better caregivers. Come on in. We're going to talk about this some more. This is hope for the caregiver. Come back and be healthy with us.

We'll be right back. God. That understanding, along with an appreciation for quality prosthetic limbs led me to establish standing with hope for more than a dozen years. We've been working with the government of Ghana and West Africa, equipping and training local workers to build and maintain quality prosthetic limbs for their own people on a regular basis. We purchased and ship equipment and supplies.

And with the help of inmates in a Tennessee prison, we also recycle parts from donated limbs. All of this is to point others to Christ, the source of my hope and strength. Please visit standingwithhope.com to learn more and participate in lifting others up. That's standingwithhope.com. I'm Gracie and I am standing with hope. Welcome back to hope for the caregiver.

This is Peter Rosenberger. This is the show for you as a family caregiver. One of the things that we talk about on this show a lot is the concept of the caregiver versus caregiving. We're not here to really get into the nuances of caregiving. We'll swerve into it periodically, but it's not high on our list of things because those are one and done issues. For example, giving an injection, changing a dressing, fighting with an insurance company, learning to deal with doctors.

All those things can be learned and you got it and you're off to the races. You got it. You know what you're doing. But with the heart issues of a family caregiver, those things require repeating over and over and over. I have caregiver amnesia and I've been doing this for 35 years. If I have caregiver amnesia, I'm pretty sure I'm not the only one.

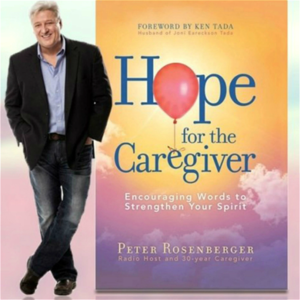

These are things that I need to be reminded of and I have found that my fellow caregivers need to be reminded of and we get disoriented of this. When I wrote my book, Hope for the Caregiver, I didn't realize quite how... Where's that available by the way? Oh, it's available wherever books are sold. Thank you. And the audio book. It's on Amazon through Audible.

But wherever books are sold, you can get this book. But when I came up with this, the publisher said, well, what are we going to say to caregivers? What do you want to say? And as I wrote this, I was thinking about what would I say to myself, the younger version of myself? And I came up with this concept called the fog of caregivers because I thought, what do caregivers struggle with the most? And I landed on the place that we struggled with fear. We struggled with obligation. We struggled with guilt, the fog of caregivers.

And evidently that really resonated because it's caught on and people have responded to this across the country with that concept because it bears out truth at any given point. And sometimes you're going to deal with all three at the same time. Sometimes you're going to just deal with a couple of them.

But you're going to deal with this. And like this woman felt obligated to go to the nursing home and we talked about it in the A block. She also felt guilty if she couldn't get there. This other woman felt obligated to take care of her brother and she felt guilty if she didn't do what she said she was going to do to her mother. All these kinds of things happen. And then all of us know the fear of it. Okay, what are we going to do about this? How's this?

What are we going to do? And so I wanted to spend a little bit more time heading to the bottom of the hour here with just that concept of being disoriented. John, you are certainly no stranger to driving.

That is correct, yes. When you approach a fog, what does the National Weather Service and all the driver manuals state for you to do? Oh, they say turn on your high beams and accelerate. Oh wait, that's what not to do. Do that one time. It's self-correcting.

One time. Yes, absolutely. No, they take your foot off the gas, you know. And what do you do about your lights? Oh, you keep them low. You don't turn on those brights.

They'll reflect right back in your face and you can see absolutely nothing. But we're straining to see far ahead and we can't. We have to be content with seeing just in front of us and we have to go slow enough to be able to deal with it.

Now, that to me is the journey of a caregiver. Whether we like it or not, the only safe way to navigate this thing is to slow down enough without trying to project too far into the future. John, have you ever done that?

Have you ever tried to project far into the future? Oh yeah, I think everybody's tried to do that a little bit too much. I mean, that's what we do when we're kids. We think about what life's going to be like when we're growing up.

My daughter's going through this right now and she's getting way out ahead of herself. And, you know, it's pretty easy to talk it down because it's small things. It's the problems of an adolescent at this point, which, you know, I've been there. So, you know, we can say, hey, let's just calm down just a little bit.

But I want to mention something. You said we have to be content with just being able to see what's in front of us. And I think that some people might argue with that, but I would definitely come down on the idea that, yes, we do. It's incumbent upon us to be content sometimes. It's an interesting word to choose for that because we're not going to be able to stress our way into a better existence. I've tried. And, you know, it doesn't mean you don't plan for the future. It doesn't mean you don't make arrangements and planning and so forth, but you don't live in it. And this is where I am today.

And I'll share why these principles are real and up close and personal to me today, right now. Gracie is dealing with a significant medical decision point. Her back is just trash. She's an orthopedic train wreck. And there's some repairs that need to be done to her back. But in order to do it, it's a very, very big surgery. I mean, a really big surgery. And she's no stranger to back surgeries, but this would be the biggest surgery she's ever had. And that's saying something because she's had quite a few, 80 to be exact.

Well, I don't even know if that's exact anymore, but she's had quite a few. So, we met with a neurosurgeon this week and so forth. And Gracie and I were having the conversation, you know, and she started saying, well, what about such as, and I said, we're going to stop right here. We're going to take this in five stages. Stage one is, can you do the surgery? Can the surgery be done to you?

Are you able to survive this? Should you do the surgery? Will you do the surgery?

When will you do the surgery and where will you do the surgery? And those are the five, in that order, we're going to answer and we're still at the, can we? And so, I'm not going to borrow the pain of when and where because we're still at the can and we hadn't even got to should. And this is the lesson I've had to learn painfully, painfully had to learn this lesson repeatedly. And I don't want to mess it up this time around.

I want to learn how to just enjoy the day, enjoy the moment and deal with today and deal with today as best as I possibly can. Because if I allow myself to live out into all these disasters that I can concoct in my mind, and I believe me, I can concoct Hindenburg level disasters. You know, then I will just be a train wreck.

I'll be a miserable person. And I read a quote from, oh, I can't remember who said this, John, I should have written it down. You would have liked to known who this was, but he said, I've had many terrible things in my life.

Most of them never happened. And I really, really resonated with that because I thought, this is where we as caregivers live is in this horrific place of carnage that hasn't even happened. And I don't want us to go there. I'd like for us to learn to just be today. And like you said, John, be content in this moment. And the only way to do that is to slow down and turn off the high beams. Slow down and turn off the high beams.

Quit trying to see further than this fog is going to allow you to see and look at where you are and slow down enough to react to it. Those are my thoughts on this subject. We're going to talk about this some more when we come back. This is Peter Rosenberger. This is Hope for the Caregiver with John Butler, the Count of Mighty Disco, because he's so tall. Don't go away. We'll be right back.

a teenager. And she tried to save them for years and it just wouldn't work out. And finally she relinquished them and thought, wow, this is it. I mean, I don't have any legs anymore.

What can God do with that? And then she had this vision for using prosthetic limbs as a means of sharing the gospel, to put legs on her fellow amputees. And that's what we've been doing now since 2005, with Standing with Hope.

We work in the West African country of Ghana. And you can be a part of that through supplies, through supporting team members, through supporting the work that we're doing over there. You could designate a limb. There's all kinds of ways that you could be a part of giving the gift that keeps on walking at standingwithhope.com. Would you take a moment to go out to standingwithhope.com and see how you can give?

They go walking and leaping and praising God. You could be a part of that at standingwithhope.com. As a caregiver, think about all the legal documents you need. Power of attorney, a will, living wills, and so many more. Then think about such things as disputes about medical bills. What if, instead of shelling out hefty fees for a few days of legal help, you paid a monthly membership and got a law firm for life? Well, we're taking legal representation and making some revisions, in the form of accessible, affordable, full-service coverage.

Finally, you can live life knowing you have a lawyer in your back pocket who, at the same time, isn't emptying it. It's called Legal Shield, and it's practical, affordable, and a must for the family caregiver. Visit caregiverlegal.com. That's caregiverlegal.com. Isn't it about time someone started advocating for you? Welcome back to Hope for the Caregiver.

This is Peter Rosenberg. This is the show for you as a family caregiver. We're so glad that you were with us.

That's Gracie from our CD Resilient. Go out and get a copy of that today. Hopeforthecaregiver.com. You figured out how to do that out there.

It's very easy. You just get involved in the show, support what we're doing here. With your tax-deductible gift, we'll send you a copy of Gracie's CD, and I think you'll find it very meaningful. John, I want to address something that we've been talking about throughout the show, and particularly the opening monologue, all the way through, and this guilt and that fog of caregiving. And I want to put it in context of something that's going on right now. I heard this story this week.

Police officers were called out. This is somebody we know, and they have a son who has significant mental issues going on. He's been diagnosed with several mental illness issues.

He does live alone, but there's some restraints there and so forth, but it got out of hand. And you've been seeing in the news a lot where cops seem to have more training. And I get that. That's an important conversation to have, just not on this show. But I do want to address one specific issue, because there's a recent survey showing a lot of calls from police going to the Middle Hill.

And I talked to a friend of mine who's a retired Seattle police officer. He and I talked about this a lot, and he thought what I'm about to offer had some real value, and it was so simple, and yet it's right there. There it is. Oh my gosh, it's so obvious.

Well, the obvious becomes obvious right before it becomes obvious. And you can do a training program, then you have to have a curriculum. You have to do this. So I've got a very specific training thing I would like to offer in this. And for any law enforcement officers that are listening, this may or may not be helpful, but I think it will be. It's with all these repeated calls to homes of the mentally impaired, or maybe it's an alcoholic addict impaired or so forth, cops are put in positions where they've got to be more than just police officers.

They're having to be all kinds of things and so forth, and it's overwhelming to already overwhelm a group of people. But there's always one participant at the call or the aftermath of this event that seems to be largely ignored, and that's the family caregiver. They're somewhere around there.

They may not be up close, but they're somewhere around there. And the thing that comes to mind is the case of Nicholas Cruz down in Broward County in Florida. Those sheriffs came out to the house 39 times. They knew this kid.

And between 2010 and 2017, he was there 39 times. And then after his, of course, he was the one that shot up Stoneman Douglas High School. And the question I had to ask is, who made the phone calls? And from everything that we could see, most of those calls originated from his mother. She was his adoptive mother.

And they kept coming to the home. Three months after she died in November, he unleashes all this hell on this school. And everybody knew that he had a problem, but did they recognize that maybe she had a problem too? And I'm not talking about necessarily mental impairment, but maybe living in that kind of relationship with somebody who was this out of control was really taking her down a dark path. And was she able to emotionally or mentally see her way through this to see how she could provide leadership and help to this young man? Or was she completely overwhelmed? Was she getting help outside counsel for herself?

I don't know. We don't have that information, but I do know that in the aftermath, and this cost absolutely no money, nothing, but in the aftermath of a call to the home where there is a mental impairment, things have settled down. If they say these two sentences to that caregiver, this seems to be taking a real toll on you. Please give some serious thought to getting counseling and help for yourself, regardless of what happens with your loved one.

Just those two sentences. They don't have to take it. In fact, they may not take the counsel, but at least you're giving them a fighting chance of where safety is and to recognize that this thing is having a negative impact on them personally. It's not just trying to get your loved one to stop acting out.

It's for you to be in a healthier place no matter what they're doing, because the healthier you are, the more counsel and guidance and leadership you can show to this circumstance that's going on with a loved one. That's just my initial foray into that. John, what are your thoughts on that? Well, that sort of thing, making sure you're getting help for yourself and getting some counseling. There needs to be, well, there doesn't need to be.

I would recommend follow-up visits like that. The other thing, I know this is Mother's Day, but one thing that we see with a lot of that, like this mother was there taking care of this deeply troubled young man, and I heard no mention of a father at all. He had died some years before that. Oh, okay.

I may be mixing these up, so never mind. These were adoptive parents. They had adopted him, and the father had died sometime before this.

Gotcha. And the mother was kind of on her own with this kid who was clearly spiraling out of control. Yeah, and that is just, yeah, because she clearly could not handle this. Most of the calls that I've talked to, and I've talked to this cop about it, and I've seen this, I've kind of done a little bit of independent research on this, that there seems to be this overarching drive, if we can just control this person's behavior and they're not acting out, then I can be okay.

And I don't subscribe to that. No, there's more going on there. I mean, that'll certainly help. It's not going to, you know, if they weren't in this situation, then the situation would be different, of course. Your personal well-being cannot be attached to this person acting out.

Yeah, yeah. Whether they do or don't. Yeah, and so if you're not physically healthy, emotionally healthy, you know, spiritually, financially, professionally, all these things going on, you run the risk of their sickness taking you down with them. And so I'm just thinking, if police officers are being called to these scenes more and more, and I talked to this police officer and he said, yeah, we keep getting called. And a lot of times it's the same house and we're like, okay, what's the problem now?

And so I'm just saying in the aftermath, when you're doing a mop-up, you know, with the report, okay, here's what we did. And then that, whoever's ringing their hands at the scene, somebody's ringing their hands somewhere. And whoever's doing that, just turn to them and say those two sentences, this seems to be taking a real toll on you. Please give some serious thought to getting counseling and help for you, no matter what happens with them. And that in itself, it costs nothing to say that.

There is no fiscal note attached to that. Yeah, yeah. And it's very difficult to do because they are not the focus of this call. They're not the one that, you know, they may be the reason that they finally, that somebody made a call, but they're not the reason that the call was made. But they can play a huge part in providing leadership for this loved one.

If they're not ringing their hands anymore and they're in a strong and healthy place, then they're in a much better situation to help this, this love, this troubled loved one, get to the help they need. Right. And it will mean less calls for the police.

And I'm sure they would like that too. Then you possibly, quite possibly enlist a healthier ally in addressing this growing problem. So my thoughts for today, uh, we'll talk about that. How about we just open this up with another show on this topic, John, because I think this is not going to go away, but we'll talk about it some more. Healthy caregivers make better caregivers.

That's the principle. This is Peter Rosenberger, hopeforthecaregiver.com. This is John Butler and I produce Hope for the Caregiver with Peter Rosenberger. Some of you know the remarkable story of Peter's wife, Gracie, and recently Peter talked to Gracie about all the wonderful things that have emerged from her difficult journey. Take a listen. Gracie, when you envisioned doing a prosthetic limb outreach, did you ever think that inmates would help you do that?

Not in a million years. When you go to the facility run by CoreCivic and you see the faces of these inmates that are working on prosthetic limbs that you have helped collect from all over the country that you put out the plea for, and they're disassembling, you see all these legs, like what you have your own prosthetic legs. And arms, too.

And arms. When you see all this, what does that do to you? Makes me cry because I see the smiles on their faces and I know, I know what it is to be locked someplace where you can't get out without somebody else allowing you to get out.

Of course, being in the hospital so much and so long. And so, um, these men these men are so glad that they get to be doing, um, as, as one band said, something good finally with my hands. Did you know before you became an amputee that parts of prosthetic limbs could be recycled? No, I had no idea. You know, I thought a peg leg, I thought of wooden legs. I never thought of titanium and carbon legs and flex feet and sea legs and all that. I never thought about that. As you watch these inmates participate in something like this, knowing that they're, they're helping other people now walk, they're providing the means for these supplies to get over there.

What does that do to you just on a heart level? I wish I could explain to the world what I see in there. And I wish that I could be able to go and say, this guy right here, he needs to go to Africa with us. I never not feel that way.

Every time, you know, you always make me have to leave. I don't want to leave them. I feel like I'm at home with them. And I feel like that we have a common bond that I would have never expected that only God could put together. Now that you've had an experience with it, what do you think of the faith-based programs that CoreCivic offers? I think they're just absolutely awesome. And I think every prison out there should have faith-based programs like this because the return rate of the men that are involved in this particular faith-based program and the other ones like it, but I know about this one, is just an amazingly low rate compared to those who don't have them. And I think that that says so much.

That doesn't have anything to do with me. It just has something to do with God using somebody broken to help other broken people. If people want to donate a used prosthetic limbs, whether from a loved one who passed away or, you know, somebody who outgrew them, you've donated some of your own for them to do. How do they do that? Where do they find it? Oh, please go to standingwithhope.com slash recycle standingwithhope.com slash recycle. Thanks, Gracie.

Whisper: medium.en / 2023-11-19 07:49:58 / 2023-11-19 08:05:18 / 15