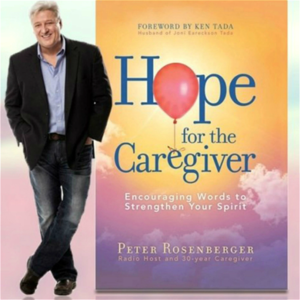

Welcome back to Hope for the Caregiver. This is Peter resilient and I love listening to her sing and glad to have her as my bumper music. That's a good thing about having your own show and a wife who's a world-class singer. You get to have her for your bumper music. So Hope for the caregiver.com if you want to see more about her CD.

We're glad to have you with us. This is the show for caregivers, about caregivers, hosted by a caregiver, bringing you 35 years of experience as a caregiver to help you stay strong and healthy as you take care of someone who is not. John, I've got a guest on the line here that I saw her column in the New York Times, her opinion piece in the New York Times, and it is a fabulous piece that she's written and you can tell she's a very good writer and she's a wonderful. In fact, she does this for a living, John.

Oh, okay. She's the restaurant critic. Kate, did I get that right? Are you restaurant critic, food critic? What kind of critic are you? Yes, I'm a restaurant critic.

I live in Sacramento, California, where I live. I'm an amateur restaurant critic, Kate, but it's usually things like Taco Bell or something. But you took on this topic of unpaid family caregivers in the New York Times, and this is part of an overall arching focus that you have through your new book. It's called Already Toast. So we're carrying on the food theme, is this correct?

Well, yes. This book comes out, I believe, in March, and it's called Already Toast, Caregiving and Burnout in America, and we're welcoming Kate Washington from the great state of California. So Kate, thank you for taking the time to call the show and just share your thoughts and your heart and your journey. When I read your article, I got to tell you, Kate, the first thing that came to my mind was I wanted to call you up just to make sure you're okay.

Because you've had a journey there, haven't you? Thank you. It really has been a journey. I'm really fortunate, and thank you, I should say, for having me on.

I really appreciate the invitation. Sure, sure. It has been a journey. It is easier now than it was at the time that I cover in that article. The intense period of his need for caregiving was over the following couple of years, and then his needs have kind of ebbed and flowed since then.

He does have chronic illnesses residual from his treatment, but he's doing much better now. So we're very fortunate that that is the case. Well, and you were fairly candid in this article and in your book of just how dark this place took you. I mean, you went down some very, very, very painful places that a lot of people don't necessarily share in their journey as caregivers, and you did it.

And you know what? I think because you're such a wonderful writer, you did it in a way that had, I'm not going to say this right because my language skills are still developing, but there was an elegance to the way you described the descent, if I'm saying that correctly. Does that resonate? Well, thank you. I mean, I take that as a very high compliment.

I really appreciate it. Yeah, I mean, it was a very, very challenging period. His life was in danger for an extended period of time. And I was really fortunate to have family and community support, but what I found along the way is that even that, the level of support that I was really fortunate to receive doesn't always alleviate the challenges that can come with really intensive caregiving. You know, that I really firmly believe, and I came out of this journey really believing that we have a strong need for more structural support and more systemic support to really give this important work the support that it deserves. Well, from the last figures I looked at, we as family caregivers provide about $500 billion of unpaid care every year.

That's a figure I looked at, and that's an astronomical amount of labor and unpaid care. And I was looking at some of the things that you're laying out in your article, and you open the conversation up more in your book, but it's basically pushing on the Biden administration to look at this thing and $5,000 a year tax credits, that kind of thing for family caregivers, which I think would be really wonderful. I'm looking at my 35 years of this and I'm thinking, hey, John, that would be helpful. Is that retroactive? Yeah, are you thinking retroactive, Kate?

Because I've been doing this since the Cold War, man. Dream big. But I also think there's such a cost with people who step out of the workforce or reduce their work hours, that some of the hidden costs of losing out on contributions to Social Security and other kind of lifetime costs that accrue over a long caregiving journey such as yours. We are a huge population, and the value of that work, I think the figure that you quoted really shows how radically undervalued care of all types is.

I think it also really needs to start simply with paid leave for people, that that's not guaranteed really to anyone in the U.S., and we're one of the very few countries where that's the case. Well, and I don't know how that will work out, and I want to say I've had people that have talked about this on the show before. And, you know, as as Congress, which moves at half the speed of smell anyway, you know, as they debate this, we've got to live today. And we, you know, they're I'm a caregiver today. You're a caregiver today.

And so we've got to deal with what the reality is and hope that we can use our voices to kind of form a pretty good choir that would hopefully resound with these folks and change the way they look at this vast army, invisible army often of unpaid people that do. I mean, I have performed and I know you have, too, because of the nature of your husband's illness. I performed complex medical tasks that I had no formal training for. And, you know, just 10 years ago would be done by an RN. And now they're getting a guy that's got a music degree to do it, you know.

Absolutely. I don't know what they taught you. Did you have your doctorate? Did I understand that?

I do. I have a doctorate in English literature. So, you know, when they call for the doctor on a plane, I'm only good if you have an emergency and like interpreting tickets. We have a grammar situation here.

Does anybody know this particular sonnet? I'm the wrong kind of doctor for the sort of tasks that you're describing. And I think that's more and more common for caregivers. And it's a really hard piece of the puzzle for people, you know, that we're frequently, it's just kind of assumed that that will take over fairly complex care. And I think it can be really frightening, you know, and people rise to the occasion and it's amazing, but it's a hard thing, I think, to face. It certainly surprised me. Well, and I want to throw something out at you.

We don't rehearse the show, clearly. But no, I mean, we're caregivers, so we know the topic. But I rose to the occasion and really threw myself into learning a lot of things that were way beyond my skill set. And I was able to do some things and I was able to give the appearance of being able to do some things. But in reality, I should have been cautioned more.

I should have had trained professionals looking at me and saying, slow down. This is not really yours to take. It's OK for you to push back and let them come up with a solution.

Let the doctor come up with a solution for this. That doesn't involve you just give it willy nilly, abandoning your life or throwing yourself into this. How do you how do you respond to that? Does that resonate with you at all?

Yeah, I mean, that's that's that's an interesting point. I think, you know, there's an authority issue around, you know, major care situations where, you know, I think if you're one person faced with a, you know, a panel of doctors discharging somebody you you love more than you love anybody else and that you're willing to do anything to try to help. And it's pretty hard to to push back and say, like, I can't do that.

I can't do that for this person. You know, and there are a lot of expectations. It's it's a very challenging and tricky issue because, of course, we all want to do our best for the people we love. And, you know, for me, I wanted to care for my husband and I was surprised by how hard it was on me.

And sometimes didn't like to admit that and, you know, tried to. Look competent, be trustworthy, seem at the doctor's office, like somebody who was taking notes and had it together and was going to to do a good job in part to get that respect and that kind of collegial relationship that I think is really important. And there's a lot of there's a lot of pitfalls and challenges there, but what you're saying, you know, it does it does resonate. I think there's a need for. You know, the medical profession as a whole to kind of step back and say, like, what are we asking people to do?

And is that in the best interest? Not just of the caregiver, but of our patient that that would have been very helpful to me in many cases, just because I could do something doesn't mean I should do something. And and I I've wrestled in all the I remember a reporter asking me one time, what is the what is the single most difficult thing you face as a caregiver? Now, my wife's had 80 surgeries and both her legs. She lives with she's an orthopedic trainer, lives with lots of pain, 100 doctors, 12 different hospitals.

I mean, this has been and it's ongoing at 150 smaller procedures. That's my resume as a caregiver. That was part of it. And yet the hardest thing for me, Kate, was learning what is mine and what is not mine to carry to do. And I overstepped many times. Did you struggle with that? Did you struggle with overstepping? Or do you struggle? Yeah, I think I did.

I think so. And I think that that's something that I think often too can come up between spouses, you know, or in care situations where there is a question around, you know, the patient's wishes, the care, you know, the caregiver's view on the situation. Yeah, jumping in and and trying to take on too much or having a hard time accepting, accepting help. I would say I struggled with all of those issues. And, you know, in part, that's why I wrote the book is to to shine some light on how hard all of those elements of caregiving can be and help people feel like they're not alone and like they have permission to, you know, be in that struggle and to take the help.

And to use the community and and move through those hard times despite the struggle. Well, and, you know, you're a formidable person. I mean, you're highly educated. You're incredibly articulate. You've got a verbal authority that you have about you.

And it's, you know, I found and I was a strong personality throughout these things, still am from what John tells me. And, you know, I remember, you know, when your last your last name is Rosenberger and you show up at a hospital and you speak the jargon and you're wearing a suit, you get called Dr. Rosenberger a lot. And I always tell him I'm a cranial proctologist.

And never just, you know, Peter Rosenberger, cranial proctology. But I, I assumed more than I should have. And I had to learn to sometimes bite my tongue and learn to like the taste of blood. And because there were some things that I needed to stay out of, I used to insert myself into conversations and the doctors found it much easier to deal with me sometimes and deal with Gracie, but they really needed to deal with Gracie.

And she needed to have agency over her life. And I stole some of that from her. I didn't mean to be a jerk about it.

I just did it because it was expedient. I was in, I was in problem solving mode. And sometimes it's important for me to insert myself and sometimes it's important for me to just hang back. And that is, boy, there's so much tension with that with me, that conflict. And I mean, I'm 35 years into this and I'm still struggling with that.

And so as I was reading your book and I was thinking, well, here's somebody else who, who gets that level of high pressure, high intensity of, okay, where's my place in this? And, and finding sure footing. That was a hard place for you, wasn't it?

To find sure footing. Yeah, I would certainly say that it was. And there was a, the most intense and difficult period around that I would say was in the months following my husband's stem cell transplant when he was hospitalized at length. And, you know, he, as I'm sure you're, you've had experience with, he was on a lot of medications, he was in a lot of pain. And there were often judgment calls or things that he felt very strongly about that I wasn't so sure.

And I really struggled with the line between like, how do I treat him, you know, like my partner and, and this man who had his own consciousness while also acknowledging that he may not be in his best place of judgment because, you know, he was so ill. And that was a hard, hard lesson to learn to step back, you know, and then as he's gotten better and had an easier time stepping back, you know, again, and not seeing him as a patient anymore, even when he is sometimes a patient is, continues to be a challenge. I get it. I get it. You know, you and I both speak fluent caregiver here and I'm watching Facebook people right now.

There are comments on Facebook. I just want to give you one from a lady, a friend of ours, and she's just saying, I hear exclamation point. I hear her. And so I love that. We're talking with Kate Washington. Her new book is called already toast, and it talks about caregiving in America. And she's just a wonderful individual who's, who's understood the journey in ways that I hope that others never have to. And we're gonna be right back. Don't go away. Kate Washington is with us.

Her new book already toast. 24 seven emergency support, increasing safety, reducing isolation. These things are more important than ever as we deal with the challenges of COVID-19. How about your vulnerable loved ones? We can't always check on them or be there in ways we'd like. That's why there's Constant Companion seamlessly weaving technology and personal attention to help push back against the isolation while addressing the critical safety issues of our vulnerable loved ones and their caregivers. Constant Companion is the solution for families today. Staying connected, staying safe.

It's smart, easy, and incredibly affordable. Go to www.mycompanion247.com today. That's mycompanion247.com. Connection and independence for you and those you care about.

Mycompanion247.com. Have you ever left the stove on? I'll be honest, you know you have.

We all have. And the smoke fills up the kitchen, the smoke detector goes off, the dog starts barking, the phone is ringing, and there's pandemonium everywhere. How'd you like something to avert that? Well, there's a new invention called fire avert, and it plugs in to your stove, and it pairs with your smoke detector. And the moment the smoke detector goes off, it shuts off the heat source to the stove, gas or electric, and make sure that it doesn't turn into a fire. We have a lot of things going on all the time, and a kitchen fire is not on the list of things that we need to be stressed out about. Let's take that off the table.

And what about your loved one who's living alone? Or what about families with a special needs child who may accidentally leave aluminum foil on the plate, put it in the microwave, or a fork on the plate, and it starts smoking up? These are things that we can avert with fire avert. F-I-R-E-A-V-E-R-T. Go out there and look at it today. It was invented by a fireman who got tired of being called to homes and seeing all the damage that could have been avoided.

And so he came up with a great idea that did this, and guess what? It's working, and hundreds of thousands of homes across the country are using fire avert. Let yours be one of them. FireEvert.com. F-I-R-E-A-V-E-R-T.com. Use the promo code CAREGIVER and get an even greater discount than the already low price. It's a great gift to give to yourself, to a loved one, and to a caregiver you know.

FireEvert.com. Promo code CAREGIVER. He will be strong, but he will never be saved. The joy of the Lord is my strength. The joy of the Lord, the joy of the Lord, the joy of the Lord is my strength. Welcome back to Hope for the Caregiver.

I am Peter Rosenberger. This is the show for you as a family caregiver. That is Gracie with Russ Taft, who's been on the show.

Gracie, Grammy Award winning, double award winning Russ Taft, and he just had knee surgery himself. John, I'll tell you, this getting old is not everything it says in the brochure. I will tell you that.

It's not for wimps, I'll tell you that. I wish Russ all the best there. And we're on the line here with Kate Washington. Her website is K-A Washington dot com.

That's K as in Kate, A as in A Washington dot com. And her new book is called Already Toast, and it's talking about the plight of caregivers in America right now. And it's it's a it she goes into a a difficult journey that she and her husband have had through some very, very serious illnesses.

And she doesn't pull any punches and she kind of lays out what she feels like would be a roadmap in her new commentary in The New York Times of some things that the administration can do that our elected leaders can do and lays it out from a caregiver's point of view. Kate, I will. One thing that struck me in your book when you had a you go to these doctors, you're already tired, you're worn out, you're scared, you're you're you're you're in the midst of that that what I call the caregiver fog, fear, obligation and guilt. But you're just in in that place where you're just so struggling. And the doctors, you know, you need to take care of yourself. And instead of looking that as a positive thing, it felt so much like a put one more burden on me.

OK, now I got to figure out a plan for me. And I love the way you said that. I love the way you brought that up, because I think so many caregivers do that.

Well, yeah, thanks for the obvious thing there. I got to take care of myself, but I don't know what that looks like. You didn't know what that looked like, did you? No, and I mean, in some ways I did, because I'd been doing the things that are often recommended, you know, I was able to take some breaks. I had family support.

My husband's parents were incredibly supportive during the worst of his illness in particular. So I was able to take breaks. I was able to, you know, get to the gym a few times a week and some of those outlets that are often recommended. So I felt like I was doing those things and was burnt out anyway. You know, the title of my book comes from going to take a quiz about caregiver burnout online after that doctor kind of told me, you can't take care of him if you're not taking care of yourself.

And I took the quiz and it kind of popped up this little result that was like, you're already toast. Like too late, you're burned out. And I think it's very challenging to get out of that state once you're in it. And, you know, in a complex, I'm sure many, many of your listeners are in that kind of complex, difficult, ongoing caregiving situation, you know, that, you know, as your experience shows can last for years and decades.

And it's really challenging. To me, what I feel like we need to shift our thinking away from the model of self-care and toward, you know, community care and privileging care, maybe, you know, bringing in care networks, you know, mobilizing our communities to lift us up when we're at our low points and thinking about care in a less kind of siloed, nuclear family kind of model and more as a community model. But, you know, I do think all of the self-care things are valuable and indispensable, but it can be really hard to hear to add another thing to your to-do list when you're already full up on caring for other people. There's really nothing left but to, you know, collapse into bed at the end of the night when all the obligations are done.

You know, I really appreciate you saying that. I love the visual. See, I told you, John, she's just got this way with words.

She's just elegant. A silo care. Do you see silo? How many times have you heard me use the word silo on this Sean, John? I mean, show John. I mean, I don't even use that.

And I grew up in the country in South Carolina and I didn't even think to use that. You know, I just it's sad, sad. No, I, one of the passions I have, Kate, on this show is to have conversations like this with people.

We could just sit down and have a real conversation. And this is what I wanted to say to you when I was reading your article and looking through your book. And I wanted to say to you, you know, I see you and I see the magnitude of what you carry and I hurt with you. And that's the first thing that came to my mind when I was reading your New York Times piece is because I saw the pain that you were carrying. And I and I understand that level of pain and trauma. And I think it's important we have those kind of honest conversations with each other of recognizing the magnitude of what a family caregiver carries. So I thank you for being a part of this with me.

I want to pivot real quick. In just the last minute or two I have, you're still writing. You're still doing the column you have at the Sacramento Bee.

It's been a bit on hold because of the lack of restaurants. Well, that's true. Yeah. Gracie and I just watched a movie the other night, the one with Sandra Bullock, and she was the crossword writer at the Sacramento Bee. Surely you've seen that movie. All About Steve? I have not. I'll have to go look for it. You've got to see this movie.

It's your paper. But the thing is, it's so funny is Sandra Bullock plays this character who's so smart. She writes in crosswords, but she talks incessantly. And I know a person who does that. And I won't mention her name, but I'm married to her. And I looked at it and I said, I love this movie.

And Gracie's looking at me sideways. She said, don't say a word. I said, I wouldn't dream of it. But this is Cinema Giant. This is Oscar winning material here.

It's a really cute movie that came out a couple of years, several years ago, but I think you'd like it. But it's your paper. But I'm sorry that you're not able to do that.

What are you doing to stimulate that part of you? You've written a book. Are you going to do more columns too? Yeah, for sure. I mean, we still have indoor dining shut down here due to the pandemic. We didn't even get to talk about how the pandemic has affected caregivers, which is a huge issue. But I am doing some writing for them and working on some other pieces and continuing to write.

I also have two daughters who are doing their school at home and my husband, while more independent certainly than he was at the period I wrote about, does have some ongoing care issues. So I do manage to keep pretty busy with everything. I would say so. Well, you're you're you're a wonderful writer. You've taken on a topic that is so needed and you're becoming a powerful voice for those who just don't feel like they have one.

So that is a that's about the highest compliment I can pay you. And I thank you for what you're doing, Kate. The book is called Already Toast and it's available this in March, right?

Yes, March 16th. And it's available to preorder everywhere now. And I really thank you. Well, you are quite welcome. Already Toast, Caregiving and Burnout in America, K.A. Washington dot com, K.A.

Washington dot com. And Kate, thank you very much. We're going to have you back on, OK? Great. Thank you so much. You're welcome. This is Peter Rosenberger, Hope for the Caregiver dot com.

We'll see you next week. This is John Butler and I produce Hope for the Caregiver with Peter Rosenberger. Some of you know the remarkable story of Peter's wife, Gracie. And recently, Peter talked to Gracie about all the wonderful things that have emerged from her difficult journey. Take a listen. Gracie, when you envision doing a prosthetic limb outreach, did you ever think that inmates would help you do that?

Not in a million years. When you go to the facility run by CoreCivic and you see the faces of these inmates that are working on prosthetic limbs that you have helped collect from all over the country that you put out the plea for and they're disassembling. You see all these legs like what you have, your own prosthetic legs and arms. When you see all this, what does that do to you? Makes me cry because I see the smiles on their faces. And I know I know what it is to be locked someplace where you can't get out without somebody else allowing you to get out. Of course, being in the hospital so much and so long.

And so these men are so glad that they get to be doing, as one band said, something good finally with my hands. Did you know before you became an amputee that parts of prosthetic limbs could be recycled? No, I had no idea. You know, I thought of peg leg. I thought of wooden legs.

I never thought of titanium and carbon legs and flex feet and sea legs and all that. I never thought about that. As you watch these inmates participate in something like this, knowing that they're helping other people now walk, they're providing the means for these supplies to get over there, what does that do to you just on a heart level? I wish I could explain to the world what I see in there and I wish that I could be able to go and say, this guy right here, he needs to go to Africa with us. I never not feel that way.

Every time, you know, you always make me have to leave, I don't want to leave them. I feel like I'm at home with them and I feel like that we have a common bond that I would have never expected, that only God could put together. Now that you've had an experience with it, what do you think of the faith-based programs that CoreCivic offers? I think they're just absolutely awesome and I think every prison out there should have faith-based programs like this because the return rate of the men that are involved in this particular faith-based program and the other ones like it, but I know about this one, is just an amazingly low rate compared to those who don't have them. And I think that that says so much.

That doesn't have anything to do with me. It just has something to do with God using somebody broken to help other broken people. If people want to donate a used prosthetic limbs, whether from a loved one who passed away or, you know, somebody who outgrew them, you've donated some of your own for them to do. How do they do that? Where do they find it? Oh, please go to standingwithhope.com slash recycle. Standingwithhope.com slash recycle. Thanks, Gracie.

Whisper: medium.en / 2023-12-18 10:15:41 / 2023-12-18 10:27:30 / 12