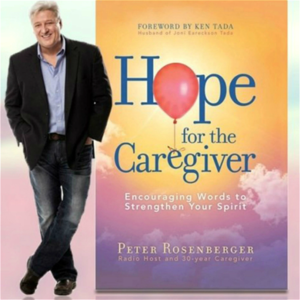

Welcome to Hope for the Caregiver. I am Peter Rosenberger, Hopeforthecaregiver.com.

This is a show exclusively for the family caregiver. We're glad that you're joining us. I love to have an interesting guest, and no one is more interesting than my next guest. He was my piano professor in college, and I still am learning from him greatly. He continues to inspire me, to teach me, to help me learn and see things differently musically, but also from a life perspective. You'd be amazed at how many things I've learned about caregiving from music theory from this man, and I'm glad to have him with us. He also played at our wedding, and then he turned around and played at our son's wedding many, many years later, and it was just such a treat to have him there. This is John Arne.

He is a retired professor from Belmont University in Nashville, Tennessee, and a great swing player, bebop player, loves the great American songbook, and also continues to push himself to create, to write, to arrange, whether it's hymns or great songs for choirs, original scores, and he's now working on his second novel. So he's kind of a Renaissance fella, and it really makes me mad because I could barely do one thing, and he's doing several, but I'm glad to have him here. John, so welcome to the show. Well, good to see you, Peter, and hello, Gracie. She said, look, if you want me to join you on camera, you have to start doing these things later in the afternoon.

Okay. And I thought, okay, well, we'll do the best we can, Gracie. All right, the reason I'm having you on today, and those who have listened to the show for some time will know these things, but I consistently reference music because that's been a big part of my life. I've been a musician longer than I've been a caregiver, and that's saying something, but I learned life lessons from this, and the other day I introduced my co-host, John Butler, who's not with us today for this interview, but I always have some kind of funny interview for him when he comes on the show, and for whatever reason, I did this. The old Henry Mancini, Pink Panther's theme.

We all know it. And as I played it, it occurred to me that I was playing parallel fifths. In music theory, 101, in the old days when we were just young heads full of mush learning music, one of the cardinal rules in harmonization when you're writing out pieces, don't use parallel fifths. But one of the things about being a musician is you learn to bend the rules.

And Henry Mancini bent that rule and bent it so well that it became iconic and did this with parallel fifths because it worked. And I made the bridge to being a caregiver. Sometimes we're locked into tradition that we don't have to abide by as caregivers. We can do things differently. We don't have to do it the way we always thought it had to be done. We could be creative. We could adapt. We could be flexible.

I don't think it's in scripture, but I think one of my favorite proverbs is blessed are the flexible for they shall not be bent out of shape. But as I mentioned that to you, you had a great comment that you said about rules and parallel fifths and so forth and about music in general. Can you revisit that for a moment? Well, since you were subjected to my theory teaching, you may remember, but knowing you, you may not.

Oh, that's cold. My thinking is that if we teach music theory as a set of rules, we're missing the boat because in terms of theory, there are no rules. So the rule of don't write parallel fifths doesn't always apply. The suggestion I would make would be don't think of those what typically are believed to be rules.

Think of them as practices, which vary depending upon what you're trying to write or what you're trying to perceive. And you along with don't write parallel fifths is don't write parallel octaves. When we all know they sound pretty good, but not in four part polyphonic music, because the goal of polyphonic music or many voices is individual voices.

And if you link up two voices with parallel fifths and octaves, you just lost a voice because the octave simply reinforces that line and makes it, if there are two lines and going on contrapuntal lines, you just lost your individuality of those lines. Well, and that brings me why this is important to us as caregivers. One of the things that caregivers lose is their own voice. I mean, it just happens.

It happened to me. I haven't met a caregiver yet that hasn't struggled with the loss of identity in their journey. What you said is so important because caregivers can maintain their own voice and in the process make beautiful music. And to give you a musical illustration for those listening.

So what he's talking about, if we just do this all the time, that's in octaves. But if you're willing to have an individual voice and you have different voices in play, all of a sudden music is made right in front of you. And this is what happens in our relationships and our journey as caregivers is that we're trying so hard to emulate someone else and do exactly what they did, but we lose our individuality in the process and we miss the opportunity to make beautiful music, even while dealing with very harsh circumstances.

This happened to me repeatedly. If you take it out of the music sense and put it in the everyday sense for caregivers, ask a caregiver, how are you doing? And the caregiver will invariably respond in first person plural or third person singular. Well, we had a bad night or she's not doing real well or our situation.

But when you ask a caregiver, how are you doing specifically? That's when a different tone will come out. And sometimes there's tears and stammering and so forth, but it's their voice and their voice is important. That goes back to what you just said. We don't want to lose that individuality.

We want to keep it so we have the beautiful music. So that's my bridge from music theory to caregiving. Yeah, I'm not near or I wasn't near the caregiver that you have had to become and do so well. But we were, and I say privilege, and I'm not trying to be self-serving here, but we were privileged to have my wife's mother, who lived to be 99. We had her in our house. And I became a caregiver looking after her when my wife was doing other chores away from the house.

And I just kind of stumbled on ways of dealing with her dementia. The main one, the simplest example is I would ask her to help me work a crossword puzzle. And I would invariably ask her, I'd give her a clue.

And I would preface that with, well, I know that you're not probably going to know this. And she would start smiling because she knew that I was wrong and that I was just saying that. And one quick anecdote was I asked her on one occasion a clue.

And I said, you're probably not going to know the answer to this, but I'll go ahead and ask you anyway. And then I asked her and she responded with what I wasn't thinking that clue was. But she was right. She had the right answer.

I was imagining the wrong answer. That was kind of a little time for us to be together. And I realized who she was at that point. And it didn't matter what she thought I was at that point.

We just had that time. And I figured that was a lot of sons in law might not be willing to make that. But I thought just like you, that's my job right now. It's not a bad job. It doesn't mean it's an easy job, but it's not a bad job.

And it doesn't mean that you can't grow and become enriched through the process. And this is my whole message to family caregivers. The predetermined outcome may be because of the diagnosis of your loved one. I was just talking with a guy the other day whose wife was diagnosed with early onset Alzheimer's. We know this is not going to end well for him.

I mean, I mean for her, but the question is, what's it going to end like for him? That's the unknown. And that's where the growth and the joy and the beauty can come about. I got to tell you, I got to out you on one story because you told me this years and years, actually you said this in class all those many years ago. I remembered it and I've quoted you often. Sometimes I did when I was on like a TV or something like that, I wouldn't source it because I didn't want to get you in trouble while your mother-in-law was still living. But I remember you told us the story of you were sitting at the table, the dinner table and your mother-in-law evidently was very opinionated. And she was talking about music and she said, well, I know what I like. And you quietly in your Bob Newhart kind of way said, no, I think you like what you know. I don't remember who first said that, but I can tell you quite honestly, I was only quoting somebody else, but it worked. Well, it did work and it was funny. And I remembered that day in class when you told us that, and it was so funny. And that was 35 plus years ago. And so I haven't forgotten that you like what you know. And I thought that was... If you remember that and you remember two, five, one, which you do, then my job... You can rest assured now, you were successful as a teacher. I remember you pushing back on your mother-in-law at two, five, one. Two, five, one, for those of you listening, scratching your head over this, two, five, one is a chord progression. And I've also talked about how this applies to us as caregivers.

I'll give you an example. You play the minor two chord and then you go to the five chord and then it resolves to the one chord. And your ear is expecting this. You expect it to go to that one chord. Where great music starts to happen is when you go to something you didn't expect. And you stretch it out and you bring in different resolutions. This is what I've learned through music theory and a lot of music and listening over the years and everything is two, five, one.

And it's all about stretching it out and doing the unexpected, resolving it in ways that you didn't expect, letting the music teach you and resolve in ways that maybe you didn't expect. This is another life lesson for caregivers. We don't have to resolve it the way we think it's going to resolve. It doesn't have to go that way. It can go a different way.

Even if it sounds like going to a minor chord, that's still beautiful music. And if we can condition our hearts a little bit to be comfortable with something different. We don't lock ourself into this rigidity of things. We can expand it.

We can see texture and color in ways that we didn't know. And that brings me to something I wanted just to spend a little time with you on. You have arranged untold amount of hymns. You and I both share a great affinity for the hymns. I remember when I was in my first year class with you and I went home to our church in South Carolina where my dad pastored and I was at the piano in the church there and I opened up the piano seat and there was one of your hymn, your books of hymn arrangements that the pianist at our church had purchased and was learning. And I said, that's my teacher. And she was so impressed and overwhelmed. And I said, that's my teacher.

You're using one of his books. And you've arranged who knows how many hymns over the years. And when you approach a hymn to arrange a hymn, and I love the hymns. I truly love them. I think it's a treasure trove of wonderful things that we have.

And sadly, all too many churches have gotten away from them. But what goes through your mind? What do you want to say musically when you approach a hymn? But what goes through your mind? First of all, and primary, I pay attention to the text and try my best ability to react to that text. Because I've written I've been involved in music so long, that part of it, I would not even call art.

I would call it craft. I know how to get from here to there. And if I think I'm on my way to this, it doesn't have to be that way. But I'll give you an example. Let's take the hymn. Well, to answer your question, I pay attention to the text.

And then I start thinking, what do I know musically that can amplify that text or color that text? Or any example I'm about to give you is give us another way to think about that. And if we have time for just one line, you know, the hymn, Shall We Gather at the River, which everybody knows. Okay, now we have all the time you need. Okay.

Okay. My thinking is that the words of the text, shall we gather at the river, and then I try in my limited way to understand what that lyric is really saying and the poetic aspect of it. For example, is the songwriter saying we're going to gather at literally a river? Well, that's cute, and all that. But I kind of lean towards, what's he talking about?

I don't think it was Fanny Crosby. So I'm using the masculine here. I think what he's thinking about is instead of a literal river, I choose to think and suggest that it's a river of life that runs through all of us, that connects all of us. And so when I set that hymn, the chord progression that you just played is what, as a matter of fact, for that whole phrase, shall we gather at the river is typically played with one chord. Well, just the tonic chord. How many beats is that? That's two measures, isn't it? Eight beats?

Yes. That's an eternity for me to dwell on one chord, as much as I love chords. So I would change the harmony and land on the cadence there on river. And so let me give you a chord progression and I'll see if you're okay.

This could get ugly. On beat one and two, you play the one chord. Now on beat three and four, you play the two minor. Now on the first beat of the next measure, play an E minor. But I'm in the key of G. Oh, okay. What key do you want me to play it in?

Play it in the key of C. Okay. So the chord progression then, for that phrase, shall we gather at the river, I turn into the one chord, the two minor seven, and then the next two beats are the three chord E minor. Okay, now, at the same corresponding part, the original progression would notably go back to the one chord, but I choose to replace the one chord with the six chord, which is a minor chord. Yeah, okay. Now, the interesting thing is, and Lord knows, we don't want to go down to your whole time with me, go down to theory lesson and the whys and wherefores. But if you played, you could play the same thing, but with no seventh chords in those four chords, only minor or major.

Well, I have to throw one and nine on the minor two, for briefly a suspension. Yes. Now, play me just the A minor chord, not the seventh chord. Okay.

Okay. Now that minor, and of course, this is another unfortunate thing that we always assume that minor is sad and major is happy. But the minute you put that seventh in that A minor chord, for me, for my ears, I get the feeling of a sort of peacefulness or warm. Oh yeah, warm. I was going to say a warm, a nice warm blanket. Or warm. And so if it's warm, it feels good. And you know that from living where you're living and coming back into a roaring fire. But that warmth corresponds from my way of thinking into shall we gather at the river. Now, the minor gives that kind of a mystery. And it is a mystery, but it's also a pleasant feeling.

And to think that let's all gather at the river. So that's, I have to be careful. Now, I threw in the seventh there. And I threw in the ninth on here. Yes.

If you put that ninth in the A minor chord and you butt it up against the C, play me a B and a C together. See, that sounds like a mistake. But it also, it adds not only the warmth of that chord, but a kind of mystery. Right.

Yeah. And if I can talk you into accepting that, then it gets theological. Or it gets poetic thinking about, this is a mysterious, wonderful thing that we're talking about.

If you buy into my interpretation of mystery, that the river we're talking, I'm talking, I'm thinking it's the river of life that connects all of us. And that's a too long example of my answer. That's important because the text does drive it. What does it say? And too many of the hymns that we've seen today were sung traditionally with a clunkiness that did not really respect the text. And I was referenced this to you the other day when I was doing Wonderful Words of Life. Well, too many times in the old days, we sang hymns like drinking songs. And I always hated that because I felt like, let's give some respect to the text here.

So when I did Beautiful Words, Wonderful Words, Wonderful Words of Life, I wanted to do it with, and if they're beautiful words and wonderful words, it seems like the music would need to compliment that. And so I threw in that little walk down there and said, this is what it means to me. Well to switch hymns on you, if I read to you the lyric, I was sinking deep in sin far from the peaceful shore.

Now, how is that set? It said, I was sinking deep in sin. Well, the reason... That's what so many of these things were arranged like. And you're the one that taught me to go back and let's look at this differently. It turned out to be more of a life lesson than I realized. Hey, let's look at this differently. There's certain music now that music has to progress and we can't always live totally in the past, but just like remembering things from your childhood, what do you remember?

I remember this and it was just very pleasant. And so you place that kind of reference into tonal centered music and hymns. Now, as much as I'll just say another philosophical thing to put in your hat, as much as I love chords and have the feeling that I've just about got that wired, how to do chords, but there's the strength in the one chord. Why are so many country songs, hardcore country songs only involve three chords, one, four and five? Well, primarily because they are the only major chords in the chord roster in any key. And the strength of the major chord is that you can play a root of a major chord on the piano and you may not think about it this way, but the other notes in the major chord are there harmonically in the overtone series. So just a single note, but this one, four and five chord is so powerful that for hardcore country songs, simplistic lyrics, you don't need any more chords.

As a matter of fact, every additional chord is a diffusion, if you will, from the strength of the key. I'll stop on that note. One of the things you taught me was, and as a pianist, this is harder than people realize.

Okay. And I want to preface that, but to play a song, in this case, a hymn, one note at a time, just one single note with one finger, play that hymn, play that melody as expressively as you can with one finger. And that may seem like it's easy, but it's not. It's really not. It takes a lot of discipline and skill and self-control because we're so used to throwing everything in this.

Exactly. And so when I started arranging hymns, I went back again to the text and then I went back to this melody, this melody that has stood the test of time and has ministered and encouraged and strengthened untold millions of these favorite hymns. And then I built the chords around that, that concept. So for example, on Jesus Loves Me. Just a beautiful melody we all know.

But then when I added to it. Now, the reason I did that is because that hymn caregivers lose their identity. And we're so busy trying to get our loved one to God. We're trying to tear up the roof and get our loved one to Jesus that we are missing the fact that we need to go too. And he loves us too. He knows us too. As caregivers, Jesus loves me.

This I know for the Bible tells me. So it's a very individual, personal song. And so what I wanted to do was take that very simple melody and make it in a way that caregivers can remember the first time they heard it, the feelings they got when they heard it, but then now hear it in a different light and say, oh, this means something to me without destroying the integrity of the song. And there was a point where early on I was trying to throw in everything I could into the arrangement to say, hey, look what I could do. But wisdom along the way musically says, hey, look what I can get out of the way of. Look what I could avoid doing. And so that's where musicality and wisdom intersect is that, okay, just because you can do it doesn't mean you should do it. And just because it sounds really cool and impressive to do all this activity, are you losing the integrity of the message of the song? And this is the life lesson I've learned as a caregiver. I was doing everything, John.

I mean, I did it everything, but just because I could do it, that didn't mean I should do it. And I had to pull back and say, okay, where's the integrity of the journey as for me as a caregiver, when I care for Gracie and so forth, what is the core mission? Where's the melody?

Where's my melody? And then I started building everything around that. And it was truly a life changing moment for me. Now that's, I know that's for some people looking to say, Peter, you are really getting way into this theory. This is how I've learned to approach it.

This is what has worked for me. And it's been a huge teaching moment for me, both musically and as a caregiver, and then into other things in life. I don't have to go and do musical gymnastics to show you how good I can play the piano. I can go back to the integrity of the song and say, hey, listen to the message of this song. It's a good song, and it's worthy of your time. And I'm going to get out of the way as much as I can, and only accept, hopefully, the things that are going to touch your heart. That's the way I've approached arrangement.

That's what I learned from you. Well, I have, my wife and I are both teachers, piano teachers. And she has a young student who wanted to learn something about jazz. And so I'm teaching him 30 minutes of their lesson.

And I would suggest this to, now, this is probably more a teaching strategy. But we have, and you made reference earlier to the American Songbook, we have thousands of songs that are very, very much fun to listen to and admire. But I don't, when I have this young man, or this young man, I think, I kind of want to learn a new song every now and then. Because I've been playing for so long, I've got a vocabulary of, I don't know, because I started to count once, how many songs do I know?

And I got tired thinking about them. And so I decided to just keep adding songs. But if I want to add a song, I look at what you and I know, a lead sheet, which is simply a melody, and the suggested chord structures and chord symbols, like piano chord symbols or guitar chord symbols.

And the first thing I don't do is try to put all that together, even though I can. I play the melody and do what you were just alluding to. The melody is what we really remember. If we like that song, and if it's a vocal, I mean, if it has a lyric with it, then we can study that lyric.

And I don't even play anything. I don't play the root of the chord and the accompanying chord. I just play the melody and listen to that because therein lies the main essence of why that song is appealing, I think. Well, this is what I've adopted as my own as well.

I love what you said. These are the suggested chords on a lead sheet. For those who don't know anything about music, and it's okay. I mean, I'm not here to try to immerse you into music theory. But Bach, for example, when you see a manuscript from Bach, that's not the suggested chords for Bach. That's what he wrote. And it's important to understand that that's something worthy of playing exactly as he wrote it.

It was good then, it's good now. With contemporary songs, jazz, blues, as we mentioned, the Great American Songbook and so forth, the lead sheet has these chords with it and those chords can change. And I've got my original book of lead sheets, it's called a real book, that I had when I was in college. And I still have his John's pencil notes over try this chord instead, try these chords instead. And I still have those pencil notes because they were not locked into that kind of rigidity. This is how I have evolved and grown as a caregiver, because I was locked into so much rigidity that I had to do it this way.

I must do this. I was listening to a guy last night who was just determined he was going to stay around the clock with his wife at the hospital who was in bad shape and he was becoming belligerent about it. Been there, done that.

Gracie's had 80 surgeries. I can't stay around the clock with her like that. It is not appropriate for me to do so because I ended up depleting everything about me. And it takes time and a lot of hard work and a lot of failure to realize, oh, I don't have to be that rigid. Music has helped soften that blow for me so that I can be as expressive.

I can adapt to be flexible and learn these things. And again, it goes back to what is the melody? What's the core essence of what I'm trying to do here?

I'm trying to care for my wife without killing myself in the process. That's the core essence. That's the melody.

Everything else then needs to support that mission. Now, this may seem pretty ethereal to connect the dots music theory-wise and all that kind of stuff, but for me, this is what's worked. And it doesn't necessarily mean it's going to work for you, but I just thought I'd spend a little time today giving you some insights into how I've evolved through this process. And I look back with cringing over the things I did in my many years as a caregiver, but I also look back and cringing at the things I did in your classroom musically when I was just banging away and throwing everything at the song and not realize that it's okay to step back and let the song breathe. Just let it breathe.

The melody was good then, it's good now. And it's okay. So how did I do that? I learned that okay? Yes. I'm not a Jedi yet. And you need to know, and I've already told you this before, and don't tear up on me, but Salome, my wife, and I have such respect and appreciation for how you with Gracie, you have managed to be the caregiver you are and extend that wealth of experience to anyone who finds themselves in that position and literally don't know what to do.

And so that's very gracious. Yeah. Well, if you don't know what to do, go back to the melody. When all else fails, go back to the melody. What's the core essence? And you're trying to care for this person you love without killing yourself in the process.

That's the melody. There it is. 24 seven emergency support, increasing safety, reducing isolation. These things are more important than ever as we deal with the challenges of COVID-19. How about your vulnerable loved ones?

We can't always check on them or be there in ways we'd like. That's why there's Constant Companion, seamlessly weaving technology and personal attention to help push back against the isolation while addressing the critical safety issues of our vulnerable loved ones and their caregivers. Constant Companion is the solution for families today, staying connected, staying safe.

It's smart, easy and incredibly affordable. Go to www.mycompanion247.com today. That's mycompanion247.com. Connection and independence for you and those you care about. That's mycompanion247.com. Welcome back to Hope for the Caregiver.

I am Peter Rosenberg. That is a track from my CD, Songs from the Caregiver. That hymn is called Near to the Heart of God. There is a place of quiet rest near to the heart of God. I did this CD specifically for my fellow caregivers just to have something just to calm your soul down to listen to. Gracie sings a couple of songs on there, but most of it's just instrumentals and a way of just hopefully providing a peaceful place for you and a meaningful musical experience. I learned how to do these hymns, these arrangements and to treat these hymns from the man I'm interviewing today, John Arnn, my piano professor from way back when in the 80s at Belmont University.

I'm glad to have him here with us. All right, I want to pivot in the last few minutes. You've written one novel. I had the privilege of just kind of coming alongside you as that thing was developing and you got it published and it's done well. Is it the sequel to that story or is it just a separate novel?

No, it's a sequel. Where I am in the process, I think I'm through. Before I turn it over to a formatter, I have this lady who is just incredible at editing and she catches everything. I think I will go to my grave not truly understanding the comma. But anyhow, Jihiwa was in the neighborhood of 30,000 words. What we're doing now here, we will take a couple of chapters and I have Salome, my wife, read aloud to me and then she catches things like, well, when did he know this?

It sounds like he already knows this, but when did he? This kind of thing. I could never do that with Gracie. I could never have Gracie read my stuff. Still to this day, it just descends into madness.

I can never do that. I've said this to Salome, but it's difficult when you allow someone to read that. She reads an incredible amount and she loves mysteries and that's what this is. It is difficult for her to not add things in. I think he would say this at this point.

Then I have to realize that I've asked her for her opinion, but I have to evaluate her concept of what the conversation is and what I think the conversation is and why her concept might be better. If it is, I'll take advantage of it. I'm no fool.

I trust there, but I now have, I just crossed over 47,200 plus words and we're only halfway through the final reading of that. Oh my. With your permission, you're not in your forties. You are now 80 years old. 81.

81. You're writing your second novel. You're still arranging, doing music, writing, composing, all these things. How important is that to you to keep your mind engaged like this? Short answer, I'm not sure.

If your question is how important is, I am sure that it's very important. It has impacted my sleeping in the sense that I will be jolted awake by some thought. I have to employ a mantra. What do you call in meditation? A word that I repeat to get back to sleep. When you say meditation, I think of the Joe Bean tune that Gracie sings.

No, meditation as in yoga position and forcing your mind to not think about anything. I try to do that and it is a struggle because I start thinking of what I want to say and what I say is, let's see, think. Well, that's the problem. I learn things and then I realize that, oh, wait a minute, I'm thinking about the novel again. I don't want to do that. It's three o'clock in the morning. I'm not going to get up out of bed and write down some clever anecdote to use in the novel. I try to go back to sleep. I have a couple of things that I repeat over and over again to force my mind to shut down as far as anything else. I've come up with some pretty good stuff at two o'clock in the morning and been able to remember it. You're alluding to the fact that despite my youthful appearance, I am 81, but my mind, I have the typical older age ability to not think, can't remember some things. But I can, at that time, I will remind myself of what I was thinking and take care of it in the morning. I look at the way our society ages and I cannot stress enough the importance of working that muscle in our mind and music and writing and things like that are an important part of how I do it.

Again, I learned from you and I've watched you. I was watching our dear friend Bill Purcell, who was my advisor in college and an amazing composer who recently passed away. I got to talk to him on his 94th birthday. I saw a video that his daughter posted two weeks before he died.

Sadly, he contracted the COVID virus that went down very fast and he was playing at a party. It was extraordinary what he was doing at 94. I thought, wow, if I can do a fraction of that at 94, then I have done something really amazing. I pushed myself to constantly learn, constantly keep my mind sharp. I think this is what happens with us as caregivers.

We have so much information flowing at us, but are we working muscles to increase our abilities to process or at least maintain our ability to process. Music has been a big part of that for me and writing as well. Again, I'm learning from you on it. I just appreciate all that you've taught me and I thank you for this time that we could just hang out and talk a little bit about music theory, a little bit about caregiving, a little bit about life. When your book comes out, I want to make sure we push it because you're a good writer. You're a wonderful fiction writer as well as a wonderful dancer. That's very kind of you.

I will tell you one, this is more personal between me and you. You mentioned Bill Purcell. I had such an admiration for and I lost another friend who you, I'm sure you know, within the last month to COVID and that was Jeff Lizenby. I don't know if you'd heard that.

I've heard it, but I didn't know him very well. Okay. Well, he lived to the ripe old age of 65 and got the virus. All of us are facing something that will end our life on here. I think the best thing we can do is just do the best we can and try to be good, try to be like Jesus, try to take care of people. Even if we don't like somebody, that doesn't mean we can't love them.

I've been told by another good friend. That's the best we can do. We're here for a certain amount of time. In my waning, it's even funny for me to say that my waning years, these creative things to not act on it would be a waste.

I could not agree more. The goal is not for us to like everything that we have to do or like everyone that we do them for. The goal is for us to be willing to be enriched by the journey and add, like you said, when we play just a straight minor chord, it may sound kind of sad, but when we put a seventh, we put a ninth in it, all of a sudden it feels warm and it feels inviting and it feels comforting. And may we all have a few extra minor nine chords in our life.

How about that? Well, I know we're a sense that we're about through, but one of the... I'm thinking about my producer and he's going to say, I'm going to have to edit now because you went over the timeframe, but I don't care.

That's not my concern. My concern is to be able to have this time with you and somebody who looms large in my life and has continued to reach down now through the decades and teach me when I sit down at the piano and play and I see the reaction that people have to my music. I have to remember my times with you and the way you taught me to play that melody, to think about the text. What am I trying to accomplish here? It's not to impress the audience.

It's to move the audience. And that's a great life lesson. So thank you for that. Your producer will do this even without my invitation, but my life is a constant edit. So he can make judicious cuts in my contribution to this conversation, but thank you for even offering this. Well, no, this is my treat.

I'll get Gracie on here with us one day. Maybe we can do some music, the three of us here, but this is my professor. I wouldn't say my former professor because he's still my professor, John Arnn from Belmont University in Nashville, Tennessee. He's retired from active teaching in the classroom, but he hasn't retired from teaching.

And I don't think teachers ever retire personally. I would substitute the word teacher for God. Well said. Well said. There you go.

Well, we've got to go. This is Hope for the Caregiver. I'm Peter Rosenberg. Go to hopeforthecaregiver.com for more. We hope this has been a meaningful time for you. And I want to again thank my special guest, John Arnn.

We'll see you next time. Great. This is John Butler and I produce Hope for the Caregiver with Peter Rosenberger. Some of you know the remarkable story of Peter's wife, Gracie. And recently Peter talked to Gracie about all the wonderful things that have emerged from her difficult journey. Take a listen. Gracie, when you envisioned doing a prosthetic limb outreach, did you ever think that inmates would help you do that?

Not in a million years. When you go to the facility run by CoreCivic and you see the faces of these inmates that are working on prosthetic limbs that you have helped collect from all over the country that you put out the plea for, and they're disassembling, you see all these legs, like what you have, your own prosthetic legs. And arms. When you see all this, what does that do to you? Makes me cry because I see the smiles on their faces and I know what it is to be locked some place where you can't get out without somebody else allowing you to get out. Of course, being in the hospital so much and so long.

And so these men are so glad that they get to be doing, as one band said, something good finally with my hands. Did you know before you became an amputee that parts of prosthetic limbs could be recycled? No, I had no idea. You know, I thought of peg leg. I thought of wooden legs. I never thought of titanium and carbon legs and flex feet and sea legs and all that. I never thought about that. As you watch these inmates participate in something like this, knowing that they're helping other people now walk, they're providing the means for the supplies to get over there.

What does that do to you just on a heart level? I wish I could explain to the world what I see in there. And I wish that I could be able to go and say, this guy right here, he needs to go to Africa with us. I never not feel that way.

Every time, you know, you always make me have to leave. I don't want to leave them. I feel like I'm at home with them. And I feel like that we have a common bond that I would have never expected that only God could put together. Now that you've had an experience with it, what do you think of the faith based programs that CoreCivic offers? I think they're just absolutely awesome. And I think every prison out there should have faith based programs like this because the return rate of the men that are involved in this particular faith based program and the other ones like it, but I know about this one, is just an amazingly low rate compared to those who don't have them. And I think that that says so much.

That doesn't have anything to do with me. It just has something to do with God using somebody broken to help other broken people. If people want to donate a used prosthetic limbs, whether from a loved one who passed away or, you know, somebody who outgrew them, you've donated some of your own for them to do. How do they do that?

Where do they find it? Please go to standingwithhope.com slash recycle standingwithhope.com slash recycle. Thanks Gracie. Thank you. Thank you.

Whisper: medium.en / 2023-12-28 00:28:04 / 2023-12-28 00:45:58 / 18