He'll give you hope for tomorrow, joy for your sorrow, strength for everything you go through. Remember he knows, he knows the plans he has for you. Oh yes he does, he knows the plans he has for you. Welcome back to Hope for the Caregiver.

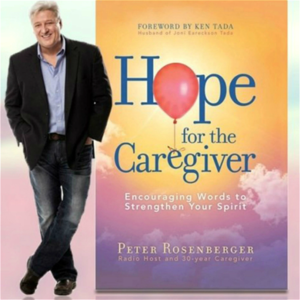

This is Peter Rosenberger. This is the show for you as a family caregiver. Hosted by caregivers, for caregivers, about caregivers, and we're glad that you're with us.

That is Gracie from her CD Resilient. You can get a copy of that today out at Hopeforthecaregiver.com. Go out there and just click on the link. You can do a tax-deductible gift to this organization. Standing with Hope, you've heard Gracie's story. We have two program areas for the wounded and those who care for them. And for the wounded is the prosthetic limb ministry.

And Gracie founded that many years ago when she wanted to take the gift of prosthetics to other people. And we've been doing that. We haven't been able to go to Africa lately because of the COVID and all that kind of stuff.

And that remains unclear when we can go back with our teams, but the work continues. We just had a little boy, John, that we sponsored his surgery for. He's 9, 10, or 11.

I can't remember. His name is Ramen, like Ramen noodles, which I survived on in college. But he lost his leg when he was four. A motorcycle, a guy on a motorcycle hit him and those guys in the Accra area in Ghana on motorcycles just weave in and out of traffic.

I mean, they're just like, you know, it's really awful. And he hit this kid and it cost him his leg. Well, as his leg continues to grow, you'll sometimes, and this has happened before, you'll get these osteophytes, these little bone protrusions out of the bottom of the amputated limb. So he couldn't wear a prosthesis and he needed surgery and we sponsored the surgery. So now that it's healing up, he's doing fine and he can go and get a prosthesis and we can help with that. But he needed some help and we felt like that was a good call to help sponsor that surgery. Again, that's one of those things where that wasn't necessarily in our mission statement to sponsor a surgery, but we adapted because it needed to happen. Right.

You had some rules that you knew about and you decided that this was not the time for that and went ahead. Yeah. And so now he can get fitted again for a prosthesis and do real well. So if you want to be a part of that, you can go out to hopeforthecaregiver.com. You can see all about what we do and just click on it and you can be a part of doing that. We're talking about obligation and obligation is part of the fog of caregivers. And I was having a conversation the other day with a friend of mine and he was asking me about the show. And what happened with the show when I started doing this, I went with some things that were core to every caregiver I've ever known.

I haven't met a caregiver yet that doesn't get lost in what I call the fog of caregivers, fear, obligation and guilt. And that leads to heartache, anger and turmoil, which put it together spells out fog hat. And so on fog hat, what do you do when you come to a fog? Well, you slow down.

And the number one song for fog hat was Slow Ride. So I try to kind of make it simple. But I found this because I got lost in this thing.

I lost myself in this. I did not know how to do some of these things and I had to run into some very tough brick walls. And I've been trying to spend the better part of all my time on the radio and speaking my books, everything else is helping fellow caregivers pry their hands off of the wheelchair or whatever it is they're gripping like out of, you know, just desperation and understand a better role for them as stewards of this and not as the end all, even though it's dire. Been there, done that.

Nobody did that for me. And I had to almost have so much trauma that it peeled my hands off traumatically of this. And so I determined I wanted to make sure that fellow caregivers understood, you know, here, this is OK for you to take your hands off of this. Your loved one has a savior. You're not that savior.

You're a steward. And there really is a difference. But that obligation. It is a really tough thing to break. It is hard. You get you get locked into this is the way it has to be. This is the way it becomes part of your identity. You know, it is. And and some people take a a real perverse sense of this. I had a lady that called in the other day. And I'll be careful on how I say this, John.

So you guide me on this. But she called in and she was taking care of her mother in law. And her mother in law was elderly, but didn't have really any kind of impairment other than she was she was pretty elderly. Other than. Yeah. Yeah.

No, no cognitive decline or or or. Yeah. But but basically they she homeschools her family.

And like pretty much everybody's doing now. But when the mother in law calls, they all jump to it. She goes over there. I said, well, have you done with this? She said, well, I just love it. I mean, you know, it's just I'm second.

I just make myself second. And she said that multiple times. And I stopped her and I felt I felt like it was appropriate for me to say. I said, you know, I've found that when you are constantly referring to yourself as second, that can lead you down a martyrdom role.

And every time this mother in law says jump, they just said, how high? And and I thought that doesn't sound real healthy. And I said, you know, I am not second and my needs are not second to Gracie's. I must be flexible. OK, I mean, I have to be flexible. Blessed are the flexible for they shall not be bent out of shape, you know, and thank you. I've heard a lot of your jokes. I think it's the first time I heard that one.

Well, but there's a true axiom. Blessed are the flexible. We need to be flexible. And I said, your kids, if they keep hearing you say, you know, I'm second, I'm second. And you have six children.

How long before you're saying I am seventh, I am seventh. And I said, maybe a better path would be to say we're learning to be flexible in this and show leadership instead of this. What we're really kind of it's almost like a sycophantic martyrdom kind of thing where you are. You're really kind of rejoicing in how much you put yourself down. Well, there is a healthy. No, it's not.

And this this bear with me, of course, because this will be a little bit of a little bit of a walk. But if I find that people a lot of a lot of people really just want someone else to be the decider. To be that, you know, they don't want to it's not a laziness thing or whatever, but they just they would really like that structure of of of of some somebody else just doing it for them or so they don't.

So they don't have to take any of the responsibility onto themselves, maybe, or for any number of different reasons. And the joke that, you know, like, well, where do you want to eat, honey? I don't know. Well, how about X? No, I hate that place.

No, I hate that place. You know, but there is a there is a certain appeal to to being second for for certain personality types, and it doesn't usually end well. So, yeah, I don't see how it could, particularly in a caregiving role where things only get into this.

This mother in law, for example, did not have any impairments. Right. But once she's trained this family to jump, as soon as she calls for it and then she starts going through impairment, she's going to be calling a lot more. You know, and all of a sudden, oh, I'm sick.

Well, I'm sick and I'm sick and I'm sick. And then also that turns into the R word, which is resentment. And then we get into a situation where we're where relationships start to disintegrate.

And and this is where I found is a huge trap for caregivers. Yeah. And I think that her not and I don't want to call it a mistake, but I think the first issue with with that mindset is ranking people at all like that.

And and, you know, we talk about what we have to take care of yourself, of course. And that's that's it's it's kind of like choosing yourself as as number one. But but even even thinking like that in terms of ranking, because there's no there's no subordination. Like you said earlier, like you have to be flexible.

Yeah, I cannot rank Gracie's needs as higher than mine or my needs is higher than hers or lower than hers. They are what they are and they're equally important. We have to have flexibility in how we're going to meet them and sometimes creativity and how we're going to meet them. Oh, yeah. And that that those are OK. And that goes back to all right, we're going to bend the rules and and we don't have to have it a certain way.

For example, let me let me because one of the things I tell these people, we say, take care of yourself and the people say, yeah, that becomes so tiresome in our ears that we just we just kind of gloss over it. So I try to paint a picture of what this looks like. Christmastime is a perfect time to to see that we must have this type of meal for dinner. We must have this.

We must have this. We must have this, you know, and all of a sudden realize, no, it's Christmas, but we're going to do it a little different this year. We're going to have maybe a smaller tree or maybe we're not going to have the Christmas goose for dinner. We're going to have, you know, tacos, you know, whatever, you know, or maybe it's just a, you know, a fold out paper turkey. Yes. And and for us, I remember when we started coming out here to Montana back in the 90s and what is the traditional Christmas dinner? Go ahead.

Name it out. Oh, like like big ham, something like that. Figgy pudding. You know, we have the the a lot of people have turkey and dressing again after Thanksgiving. They'll have these things that pumpkin pies and all this stuff. Well, when when when the boys and I and Gracie started coming out here for Thanksgiving way back in the night, I mean, for Christmas, way back in the 90s, our Christmas dinner became steaks. Really good steaks, by the way.

Oh, yeah. Twice baked potatoes and steamed broccoli and whatever, you know, and the kids would help me make the twice baked potatoes. Grayson to this day still loves to do it. And that's that's Christmas dinner to our kids. Now, that is not a traditional Christmas dinner. But we made it for us because it worked for us.

We knew what the traditional Christmas dinner was. We've had it, liked it, appreciated it. But for what we wanted to do, we wanted to do something different. And so we did. And I think that's what I'm hoping that my fellow caregivers can get out of this is understanding, you know, OK, I know this is the way it's always been done or the way you think it's always been done. But here's what we can do as a caregiver.

And somebody needs to come along and give them permission to say, you know, it's OK to to to do this. It's OK. I'll never forget, John. I was staying around the clock at the hospital with Gracie during so many of those those surgeries. And when I say around the clock, no kidding.

Around the clock. And I was sleeping that chair next to her bed. And she was.

Oh, God. And she would, you know, toss and turn or scream and groan. And doctors and nurses coming in all hours of the night and everything. And I was I was turning into a zombie.

And. But I felt like I had this was my job. I had to do it. And Gracie kept insisting that I stay there with her because out of fear, she didn't want me to leave because, you know, she was she was scared. The kids were away at grandparents and she was scared. And I was I was just I was I was drowning. Literally, I was really coming apart.

And a very, very good friend of ours, who's also a psychiatrist who blesses already helped save us. But he looked at me and he came in and he looked at me and he said, you go home right now. Go home. And I was like, no, I was he said no.

He wouldn't take any argument. You go home and you get some sleep. Yeah, we're not talking about this anymore.

There was no there was no discussion. And so and he said, they've got Gracie, I'll work with them, make sure everything's all our meds are OK and everything else. And she's going to be OK. But you go home, you get some sleep. And I went home and then. But he said something else to me before I left.

He said, Gracie, he will he will bring sunshine back into this room when he comes back. I let him go. And we were just kids. I look back and I thought, you know, I don't even know how we did this because we were kids.

Yeah. You know, I have children older than I was at the time dealing with this now. And so I look back at that lesson as a painful lesson.

It's a hard lesson. And I remember going home, driving home, and I felt so empty and I'm doing the wrong thing. I felt guilty. And then I remembered the tone of his voice. And he said, you go home. And I did. And I just out of sheer faith accepted that what he was saying was good counsel. And I did. And it changed my life. Well, I really there's something you said there that really hit a chord with me and not a parallel fifth. You know, that chord.

Yeah, no, it's probably not a diminished one either that those are weird. But he said when he comes back, he will bring sunshine into this room. And that metaphor really like so you had to you had to go out and get the sunshine. It wasn't in this room.

The sunshine was not here. You're not going to find it here. You have to go out and get it. And that sounds like an active thing.

But this was a little bit more of a passive thing. The sunshine will be obtained through this. Getting some rest, getting a good night's sleep, you know, doing all the things. But you can't you can't like I need to bring sunshine into the into this room with Gracie.

What am I going to do? I got so I'm trying to trying to bring sunshine in. You can't do it if you're there all the time because the sunshine isn't here. It's out there or it's in your bed or it's, you know, in front of a steak and asparagus. I don't know, whatever. Well, you're right. It is.

That's not its natural environment. And I have found that to be the case with way too many caregivers over the years. And if I do nothing else with this show and with my books and with everything else, if I can somehow capture what this man did for Gracie and me and put it in a way that my fellow caregivers can understand. So that they're not in that situation where they're where they're truly coming apart at the seams. Maybe, maybe I can't.

Maybe they're already coming apart the scenes. But at least I can speak into that with with the voice of experience and counsel and say, look, this ain't yours to fix. But you didn't cause it. You can't cure it.

Go get some rest. And I've got points listening on the show right now. I'm looking at him on Facebook Live watching the show that I've said those words to.

And I've watched tears well up in their eyes. But that's the journey. This is Hope for the Caregiver.

This is Peter Rosenberger. We've got more to go. Don't go away. See, all of this is about helping us stay strong and healthy and pointing to a path of safety for us as caregivers.

We'll be right back. In a dozen years, we've been working with the government of Ghana and West Africa, equipping and training local workers to build and maintain quality prosthetic limbs for their own people. On a regular basis, we purchase and ship equipment and supplies.

And with the help of inmates in a Tennessee prison, we also recycle parts from donated limbs. All of this is to point others to Christ, the source of my hope and strength. Please visit standingwithhope.com to learn more and participate in lifting others up. That's standingwithhope.com.

I'm Gracie and I am standing with hope. Twenty four seven emergency support, increasing safety, reducing isolation. These things are more important than ever as we deal with the challenges of covid-19. How about your vulnerable loved ones? We can't always check on them or be there in ways we'd like. That's why there's Constant Companion seamlessly weaving technology and personal attention to help push back against the isolation while addressing the critical safety issues of our vulnerable loved ones and their caregivers. Constant Companion is the solution for families today. Staying connected, staying safe.

It's smart, easy and incredibly affordable. Go to www.mycompanion247.com today. That's mycompanion247.com. Connection and independence for you and those you care about.

Mycompanion247.com. He will be strong to deliver me safe. And the joy of the Lord is my strength. And the joy of the Lord. The joy of the Lord.

The joy of the Lord. Welcome back to Hope for the Caregiver. This is Peter Rosenberg and this is the show for you as a family caregiver pointing you to a path of safety. How are you doing?

How's it going with you? And that's the overarching question of everything we talk about on this show is for you to be able to express in your own voice, from your own heart, how you feel about it. And in the context of, okay, yeah, I'm bringing 35 years of this to help you understand that, okay, there is a path to safety for you. And it doesn't mean that it's not going to be fraught, fraught, John, fraught, fraught, spell it, John? F-R-A-U-G-H-T. P-H-R-O-T, fraught. It doesn't mean that it's not going to be fraught with tears. And as Gametdolph said, not all tears are evil, you know, and we can, it's okay to grieve it out.

In fact, it's important to grieve it out in a healthy manner. But what happens is all too many caregivers are just wound so tight because of this obligation. We get in that fog of caregivers. We can't see straight. We can't see clearly. We don't know what we're going. And yet we are pushing the pedal to the metal. And we are full speed ahead and we don't even know where we're going.

But we're making great time. Yeah, you're on an icy road and you see a curve coming. So you just slam on the brakes. I drove back from Billings the other night. Gracie and I had to go to her prosthetist to see a man about a leg. And so we went over there to get her legs worked on. And we're driving back and there's a winter advisory. Talk about it like it's a panic, you know.

We had to put her up on a rack, rotate and balance. But the road back was pretty dicey because there was a winter advisory weather warning. Now, when they give winter advisory warnings in Montana, let me just say they ain't kids. You know, it's not a ploy to get people to go to your local grocery store and get milk, bread, butter.

Yeah, I'm going to make some milk sandwiches. Yeah, I'm in Tennessee. This is.

Yeah. In Nashville, I mean, you know, a flake of snow and everybody empties the shelves. But in Montana, you know, they mean it. And they're prepared for it out here. You learn to drive in it, but it doesn't mean it's not a little bit frightening and that the drive on the way over there wasn't snowing. And the speed limit on the interstate is 80 miles an hour, which is really more of a suggestion out here.

Yeah, they don't. There's nobody there to enforce that. But on the way back, I can promise you I wasn't going 80 miles an hour or 90 as the case may be.

I can promise you. And nobody, nobody was putting a sign up that says you need to slow down because common sense told me that road is slick and I need to slow down. And I don't slam on the brakes when I come up with stuff. I just kind of keep it easy, keep it even and not panic about it. But drive slower.

How much more so as a caregiver? I don't care what the speed limit sign says. You go at the speed you're comfortable slamming in the ditch at, okay? And if you don't feel like slamming in the ditch at 50 miles an hour, then don't go 50 miles an hour.

Well put. Slow down. Nobody was telling me to drive carefully and responsibly. There was no sign that said that. The sign said the speed limit was still 80 miles an hour.

I could have gone 80 if I wanted to. Yeah. And you have these, you know, at the risk of overusing this were these obligations and there's a little bit of pride that will get you in there. Oh, it's not just a little bit.

It's a lot. Oh, I was being kind. Yes, thank you for that because there's a perverse sense of pride that says, look at what I can do. I can bring home the bacon fried up in a pan and never let you forget it, my man. Look at what I can do.

You know, Thomas Aquinas wasn't kidding about deadly sins. Just saying. And that arrogance and pride of thinking I can do this. I got this.

No, you don't. And you are welcome to go 80 miles an hour on an interstate filled with snow and ice in the dark. And when I say dark out here in Montana, by the way, John, I mean dark. I have driven through Montana once and it was an absolute delight.

It's wonderful. Yeah, it was. As long as there's not snow and ice on the road.

Right, right. This was during the summer, so it was pretty good. But it was the darkest sky. You know, like the least light pollution I have ever been around in my entire life. And it was humbling. It is beautiful and it is worthy of experiencing unless visibility is a big part of what you got to do to keep yourself safe.

Right. Yeah, but it's dark. Then you've got to go slower and you've got to be careful. And I got to tell you, I was driving careful. I was driving slow. But when I got home, I was exhausted.

So you know what I did? I rested because I was tired. You drive 200 something miles in snow in Montana in the dark, you'll be tired.

I mean, emotionally, you'll be emotionally tired. Yeah. And so I thought about us as caregivers.

How much more so are we dealing with this? And the speed limit said 80. I could have legally gone 80 miles an hour.

But why would I want to? And so I say to you, my fellow caregivers, you can go as fast as you want to go. The speed limit said 80. Go 80. But why would you want to when you can't see very well? When conditions are treacherous, slow it down.

Especially if you're slower, like new to being a caregiver. You don't even know where you're going. Yeah, you make a great time. But where in the world are you going? You could be going right off the cliff. But slow it down. Breathe slower. Talk slower. Eat slower.

Do everything slower. There is no rule that says you have to run around like a madman. You just don't have to. And this is what I've painfully learned. OK, let's be clear.

I did not learn this smoothly. There are a lot of ditches out there with my face on it. I was going to say, yeah. You know, I did. And I've had a lot of claims to the auto club with my face on it. I hate that.

I cringe over it. OK, but here's what I've learned. Slow down. And the rules, I did not have to go 80 miles an hour. I made the circumstances adapt for what I felt like was appropriate at the time. And I went slower.

Gracie even looked at me one point. She said, why are you going so slow? And I'm thinking, you know, you had a car wreck that got us into this in the first place. Why do you want me to go faster?

You know, and then she said she realized, oh, OK, I'm sorry. You know, but but I was going slow. I was driving Miss Gracie and I was I was not.

Oh, watch it. I was not in a hurry because I needed to be safe. And I will leave you with this.

My fellow caregivers. You need to be safe, too. And I know that you don't feel safe. And the first step towards safety is often just slow down. Just slow down. OK. Breathe slower. Think slower. Talk slower. Eat slower. Slow down. It's going to be OK.

This is Hope for the Caregiver. This is Peter Rosenberger. John Butler, we're so glad that you joined us today. We'll see you next time. Oh, a program a couple of weeks from now. We got Lisa Gibbons going to be with us. So you don't want to miss that. Lots of stuff going.

Go to Hope for the Caregiver dot com. And thanks for being a part of the journey with us today. Thanks for sharing your time with us.

We'll see you next time. This is John Butler and I produce Hope for the Caregiver with Peter Rosenberger. Some of you know the remarkable story of Peter's wife, Gracie. And recently, Peter talked to Gracie about all the wonderful things that have emerged from her difficult journey. Take a listen. Gracie, when you envisioned doing a prosthetic limb outreach, did you ever think that inmates would help you do that?

Not in a million years. When you go to the facility run by Core Civic and you see the faces of these inmates that are working on prosthetic limbs that you have helped collect from all over the country that you put out the plea for and they're disassembling. You see all these legs like what you have, your own prosthetic legs and arms and arms. When you see all this, what does that do to you? Makes me cry because I see the smiles on their faces. And I know I know what it is to be locked someplace where you can't get out without somebody else allowing you to get out. Of course, being in the hospital so much and so long.

And so these men are so glad that they get to be doing, as one band said, something good finally with my hands. Did you know before you became an amputee that parts of prosthetic limbs could be recycled? No, I had no idea. You know, I thought of peg leg. I thought of wooden legs. I never thought of titanium and carbon legs and flex feet and sea legs and all that. I never thought about that. As you watch these inmates participate in something like this, knowing that they're helping other people now walk, they're providing the means for these supplies to get over there.

What does that do to you just on a heart level? I wish I could explain to the world what I see in there. And I wish that I could be able to go and say, this guy right here, he needs to go to Africa with us. I never not feel that way.

Every time, you know, you always make me have to leave. I don't want to leave them. I feel like I'm at home with them. And I feel like that we have a common bond that I would have never expected, that only God could put together. Now that you've had an experience with it, what do you think of the faith-based programs that CoreCivic offers? I think they're just absolutely awesome. And I think every prison out there should have faith-based programs like this, because the return rate of the men that are involved in this particular faith-based program and the other ones like it, but I know about this one, is just an amazingly low rate compared to those who don't have them. And I think that that says so much.

That doesn't have anything to do with me. It just has something to do with God using somebody broken to help other broken people. If people want to donate a used prosthetic limb, whether from a loved one who passed away or somebody who outgrew them, you've donated some of your own for them to do. How do they do that? Where do they find it? Oh, please go to standingwithhope.com slash recycle. Standingwithhope.com slash recycle. Thanks, Gracie. You can't get them on Amazon or you can't get them at Costco.

They're attempting to close his business because he stood up for kingdom values. What a chance to respond, especially if you need a pillow. Oh, I've had mine now for years and years and years and still fluffs up as wonderful as ever. Queen size pillows are just $29.98. Be sure and use the promo code TRUTH or call 1-800-944-5396. That's 1-800-944-5396. Use the promo code TRUTH for values on any MyPillow product to support truth.

Whisper: medium.en / 2023-12-30 07:56:24 / 2023-12-30 08:09:05 / 13